Digital masochism and the new ways we handle heartbreak

- Text by Emily Reynolds

It would be much too far to say my heart was recently broken, but it was certainly bruised. What was supposed to be a fun and carefree fling turned into something more complex, something far more knotty than either of us had been expecting: I got the sense that we had inconsistent interpretations of what had happened, that we felt the same way but about two entirely different stories.

It was an irreconcilable gap, so when circumstances forced us to discontinue contact I found myself weirdly adrift, trying to make sense of what had just happened. Part of the problem was that this man was semi-famous, so his image was too easily available to me, replicated across the internet like a strange, uncanny clone: he showed up in videos recommended by YouTube, on Instagram’s list of who to follow.

You’d have thought that this added layer of visibility would make the experience bigger, stranger, unlike other forms of heartache, and in some ways it did. But it was also surprisingly mundane, underlining an everyday phenomenon that most of us have experienced at some point: the digital masochism we partake in when a relationship ends.

This kind of self-indulgent wallowing is not just limited to the random posts thrown haphazardly and unhappily into our feeds, after all: we also look for it ourselves. There was a simple reason this man kept being recommended to me by unknowable algorithms: I’d sought him out. I’d watched his videos; I’d scrolled through his Instagram; I’d listened to his band on Spotify, careful to put my account on private mode so my followers wouldn’t know what I was doing. As my friend Suze pointed out to me, the algorithms we interact with online are mostly optimised for selling us things: “so it’s selling you your ex now”.

Clinging to intimacy via old messages is one thing. But there’s something curiously different about browsing someone’s public timeline. First, there’s often no trace of your relationship to be found in their public-facing persona, heightening your feeling of loss. In a world where so much is publicly catalogued, to experience something entirely in private can be strangely destabilising: did it happen at all?

A sense of forward movement can also be compellingly crushing, particularly if you truly are heartbroken, a state that suspends you in time for weeks or months on end. How can they be liking photos, faving inane jokes, Instagramming their view, when you’re so immersed in despair? The sense of unfairness is almost too much to bear.

Yet we can’t help but seek it out, simultaneously searching for proof we never mattered to them and reading too much into clues that probably don’t exist, hoping they were set there for us. We scroll endlessly through the Instagram activity tab to find that they liked a meaningless set of photos 8 hours ago, the information, unsatisfying, telling us nothing; we obsessively check their status on WhatsApp to see when they were last online, speaking to someone who was not us. It hurts. But that’s the point.

When I came out of hospital, two bruises unexpectedly blossomed on my skin; one, on my wrist, where a cannula had been, the other on my stomach where I’d had an injection. I treasured them. It was proof, however ephemeral, that my pain had been legitimate, that I truly had suffered, that I hadn’t exaggerated it after all.

There’s something of this in our tendency to seek out things that hurt us online. Looking at someone’s likes on Twitter, seeing their name pop up underneath somebody else’s selfie, watching them move on oblivious to your pain: it’s all part of a delicate ecosystem of masochism in which we seek to hurt ourselves, to experience that familiar ache of resentment, loss and angst.

Bruises are evidence that something happened: that what we felt was meaningful and real. Over time they fade, yes. But sometimes it feels good to press down, firmly and surely, to prove the pain is still there after all.

Follow Emily Reynolds on Twitter.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.

Latest on Huck

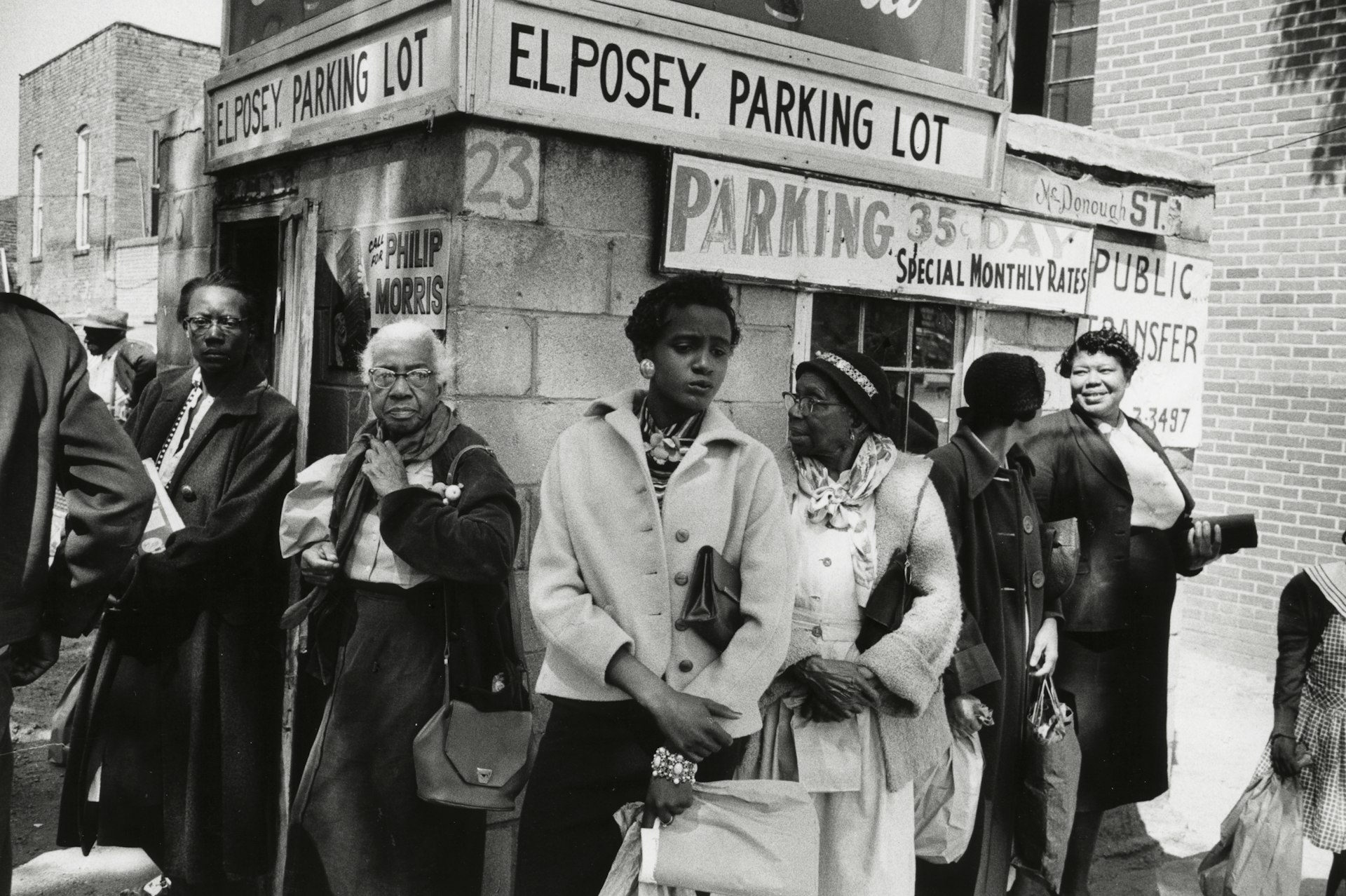

How Labour Activism changed the landscape of post-war USA

American Job — A new exhibition revisits over 70 years of working class solidarity and struggle, its radical legacy, and the central role of photography throughout.

Written by: Miss Rosen

Analogue Appreciation: Emma-Jean Thackray

Weirdo — In an ever more digital, online world, we ask our favourite artists about their most cherished pieces of physical culture. Today, multi-instrumentalist and Brownswood affiliate Emma-Jean Thackray.

Written by: Emma-Jean Thackray

Meet the shop cats of Hong Kong’s Sheung Wan district

Feline good — Traditionally adopted to keep away rats from expensive produce, the feline guardians have become part of the central neighbourhood’s fabric. Erica’s online series captures the local celebrities.

Written by: Isaac Muk

How trans rights activism and sex workers’ solidarity emerged in the ’70s and ’80s

Shoulder to Shoulder — In this extract from writer Jake Hall’s new book, which deep dives into the history of queer activism and coalition, they explore how anti-TERF and anti-SWERF campaigning developed from the same cloth.

Written by: Jake Hall

A behind the scenes look at the atomic wedgie community

Stretched out — Benjamin Fredrickson’s new project and photobook ‘Wedgies’ queers a time-old bullying act by exploring its erotic, extreme potential.

Written by: Isaac Muk

“Welcome to the Useless Class”: Ewan Morrison in conversation with Irvine Welsh

For Emma — Ahead of the Scottish author’s new novel, he sat down with Irvine Welsh for an in-depth discussion of its dystopic themes, and the upcoming AI “tsunami”.

Written by: Irvine Welsh