When graffiti is the only way to survive an urban battleground

- Text by Danielle Mackey

- Photography by Fred Ramos

Ivonne Reyes steps out of the house she rents near central San Salvador. The dark-haired 25-year-old flags down the route 2C bus, hops on and holds tight as it careens around heavy traffic, street vendors and wild dogs.

When the vehicle slides to a stop in the municipality of Mejicanos, Elize threads herself and her duffel bag of spray cans through an aisle of passengers.

Out on the street, she spots the other members of her crew, APK, several blocks away. They call out to her by tag name – “Yerly!” – ready to get together for an afternoon of graffiti.

At dusk, an old man pushing a cart of pirated CDs wanders up, tired from a day of selling in the street. He enquires about their art and what it means, surprised to find that he likes it. He asks them to paint his cart in exchange for a CD of Juan Luis Guerra songs. They laugh and complete the trade before heading home, another bystander converted.

Yerly is a leading figure among a community of street artists in San Salvador, a city with one of the highest murder rates in the world, where young people are at the centre of an undeclared war.

The streets have become a battleground; to linger in public is to invite trouble, especially in poor areas. Anyone between the age of 12 and 25 is a potential target for abuse by police, military and gangs alike.

The most common survival strategy is to prove that you couldn’t possibly be guilty of anything by making yourself appear straight-laced – eliminating all vestiges of rebellious cool and opting instead for the oxford shirts, ironed slacks and slicked hair of Salvadoran churchgoers.

Yerly sits with her son Matías at a local park, next to some graffiti she made for her husband Caesar.

A 19-year-old skateboarder recently told me what happens when the police and army descend on the Mejicanos skate park where he and his friends hang out.

One night, instead of carrying out the usual beatings, cops sent them running through the neighbourhood under a hail of bullets. The skateboarders ducked into a local’s house until the police scattered, leaving them unscathed but undeterred.

Expressing yourself on the street remains a risk some are willing to take, no matter the cost. The young grafiteros of El Salvador use the same actions that their society deems criminal – drawing on walls, working in groups, calling out the State’s bullshit – to inject art and debate into their world, transforming places of fear into spaces of engagement.

![]() Yerly’s friend TNT has been central to the country’s street art movement since early on. Born Elvi Orellana, the 28-year-old wears his hair slicked back, his moustache thin and clipped. He still lives near where he grew up: an urban municipality outside San Salvador called Lourdes Colón.

Yerly’s friend TNT has been central to the country’s street art movement since early on. Born Elvi Orellana, the 28-year-old wears his hair slicked back, his moustache thin and clipped. He still lives near where he grew up: an urban municipality outside San Salvador called Lourdes Colón.

As an eight-year-old, TNT began doodling graffiti in his school notebooks after a cousin showed him a tattoo magazine. By the age of 14, he got into breakdancing and finally landed on graffiti in 2006 with a crew called ASH. His first piece was a Superman-style ‘S’ that generated buzz.

“When people found out I was the one who did it, the connection we made was super cool,” he says in his steady voice. “I realised that’s the most fulfilling part of art.”

TNT tags the wall of a power station on the main street of Lourdes Colón, La Libertad, in full view of traffic.

Salvadoran street art was rare in the early 2000s. But then a collective of three Guatemalan artists called Guategraf visited, TNT explains, and shared enough knowledge to inspire local momentum.

In 2011, TNT launched Area503 – the first street art festival of its kind in El Salvador – bringing together 30 Salvadorans and 30 more from the wider world. He didn’t realise it at the time, but TNT was becoming a de facto street-art community organiser.

Today around 160 grafiteros attend every year with the goal of “giving local artists a space to address the problems in the region, where we have so much violence – the majority of which is committed by kids.”

Although all the organising takes time away from TNT’s own art, he believes the effort is worth it to educate others. “I’m someone who loves graffiti and is willing to do whatever is necessary to change history with it,” he says.

“But it continues to be considered vandalism, something that children should never learn. In El Salvador, graffiti has had trouble because gangs demarcate their territories with aerosol, although they clearly lack technique,” he says, chuckling. “Passersby look at youth painting a wall with an aerosol can and they think they’re gang members.”

But TNT and his peers are artists, and they want to challenge the perception that being young and poor is criminal. It’s why they make a point of going into violent neighbourhoods to teach graffiti, rather than holding workshops in neutral spaces.

Teenagers in El Salvador are marked by whatever gang runs their neighbourhood, whether they’re involved or not. Both law enforcement and rival gangs believe they have a green light to harass, beat and even kill gang members outside their home territory.

That severely restricts mobility in a city sewn with borders and battlefronts that ebb and flow every day, leaving little sense of the world beyond a well-worn path between home, school and church. For TNT, street art is a passport across those boundaries.

At a workshop in 2014, for instance, his crew showed an entire community how to paint. Nobody understood what they were doing at first, he says, but within a few hours everyone was into it, bringing out random household objects, from t-shirts to baby diapers, just to get them painted.

“They wanted us to come back every day,” he says of the neighbourhood outreach. “At the beginning, you get into this game to have fun. Then maybe you do it because you’re learning and growing. Then you realise you’re in it because of the responsibility you have when there are so many people following you, paying attention to what you’re doing, seeing you as an example. That makes you want to honour that commitment.”

![]() Despite its power, graffiti isn’t accepted by the art world in Central America. “Here, ‘art’ is directed at people who have a certain level of material comfort… ‘educated’ people who are born into good families,” says Yerly.

Despite its power, graffiti isn’t accepted by the art world in Central America. “Here, ‘art’ is directed at people who have a certain level of material comfort… ‘educated’ people who are born into good families,” says Yerly.

“What’s behind that? It’s one of the biggest problems in our country: inequality among economic classes, which I’d say causes the violence.” The walling off of resources – economic, cultural and otherwise – only perpetuates cycles of conflict. “And this is where street art comes into play: we don’t use a gallery to share our messages.”

Yerly started painting when she was an 18-year-old architecture student. A classmate introduced her to some male friends who were street artists and, one day when they were all hanging out, Yerly blurted, “Hey, let’s go paint!” The guys laughed – a girl doing graffiti? But they took her, and she never looked back.

In 2011, Yerly became official when she represented El Salvador at a small festival in Guatemala for Central American grafiteras. She decided to spend some time backpacking after that – “my rebel period,” she calls it – continuing to practise the letters now considered her specialty.

But despite having established herself as a force in the region’s street art scene, Yerly believes that being a woman means it’s hard to get people to pay attention.

“It’s definitely sexist,” she says, “starting with the four competition categories: Expert, Intermediate, Novice and Female. They always separate us out like that.”

This is something Yerly’s friend Lorena Saraí Girón Alas, aka Lolipop, knows well. The 20-year-old has two strikes against her in a field where being either young or female is a barrier. “You have to work really hard to be taken seriously,” she says hesitantly.

Lolipop

Raised in the same municipality as TNT, Loli could always be found drawing as a child. She became mesmerised by the graffiti around her house, determined to find out which neighbourhood kids were behind the magic. When she did, they shared their aerosol with her. At age 13, she joined the same crew of girls that gave her a start, GFS.

Today Loli – who’s thoughtful and serious – is one of nine members in another crew, HAKS. She’s also finishing a degree in graphic design at the Technological University of El Salvador and runs a small business on the side, selling costume jewelry and accessories for women.

Like her, the other members of HAKS are busy students, parents or office workers – all united by their passion for graffiti. Loli’s also active in neighbourhood outreach, focusing on kids who struggle to find work or stay in school – a demographic that makes them fodder for gangs.

“These are places where violence is a daily way of life and they just get used to it,” she says. “But thanks to graffiti, they start to see art as a channel, an opportunity.”

That’s not an exaggeration. Throughout 2015, I followed a young gang member as he began the process of leaving that gang and transforming his life.

In those first rough, lonely months, Juan (not his real name) often referenced one inspiration that kept him going: memories of learning graffiti and breakdancing with his former crew, the one he’d been part of before the gang.

After their leader was shot dead when Juan was just 12, he quickly folded to pressure from classmates in the Barrio 18 gang to join them and retaliate.

Now he wishes that he never responded to violence with violence. As Juan transitions back to civilian life, his memories of another way to be young and creative on the streets keep him focused.

![]() Street art became a bridge between an old life and a new one for Carlos ‘Calo’ Rosas, too. Lithe with long dreads and a radiant kindness, Calo is another early Salvadoran grafitero.

Street art became a bridge between an old life and a new one for Carlos ‘Calo’ Rosas, too. Lithe with long dreads and a radiant kindness, Calo is another early Salvadoran grafitero.

Back in 2004, while studying at the country’s National Center for the Arts, Calo discovered murals, which eventually led him to the work of more overtly political street artists like Banksy.

“The public character of urban art called to me – the ease with which things reach people when they’re outside, not in a gallery,” he says.

Before long, Calo’s signature style – portraits depicting political activists and unsung female heroes, rendered with a flair he calls “tropidelic” – was everywhere. He became a lynchpin of the community, often meeting up with the likes of Yerly, Loli and TNT around the city.

Then, like almost a third of the Salvadoran population, he emigrated with his wife to the US. Living in Philadelphia has exposed Calo to other artists’ work and given him opportunities that he never would have found at home.

“Being young in El Salvador is in itself considered a crime,” he says. “You get used to the danger, the adrenaline, but it limits your artistic development.”

Emigrating, however, presents a barrier of its own. Calo is now considered a ‘latino’ in a country where it’s increasingly difficult to be a foreigner. And although he’s nearly always smiling, his face turns solemn when describing the process of negotiating a new identity.

A portrait of activist Berta Cáceres by Calo on the streets of Philadelphia. Courtesy of the artist.

“It allowed me to see what I’m made of,” he says. “I started missing my homeland, my friends, my surf. Missing that contact with nature led me toward a new emphasis in my work: conservation and the effort to revive our indigenous culture as well as our connection with the Earth.”

The 30-year-old thinks twice about when and how he tags now that he’s an immigrant, he adds. But he won’t be silenced. Instead, Calo has brought San Salvador to Philadelphia.

Scattered about the city, under bridges and on cement posts at busy intersections, passersby can find palm fronds, the silhouette of an indigenous Central American woman or even a portrait of assassinated Honduran environmentalist Berta Caceres. “I like this about street art: the idea of making the city yours, of occupying space as a civil right,” he says.

![]() There are well-documented forms of violence that ravage El Salvador – gangs, the State – and then there are stealthier, more structural kinds: the ones that dominate and restrict daily life for young people like Yerly, Loli and TNT.

There are well-documented forms of violence that ravage El Salvador – gangs, the State – and then there are stealthier, more structural kinds: the ones that dominate and restrict daily life for young people like Yerly, Loli and TNT.

The mandate is to be silent in the face of injustices, to conform with gender roles, to forget the history that shaped your present – or else. The grafiteros of El Salvador paint new visions atop those old violences, paving the way for new social leaders – and a freer way to be young.

Back in El Salvador, Yerly is beginning her eighth year of tagging. She has met artists she admires for their talent and humility, including the man who is now her partner. She recognises that society doesn’t see her art positively and even wonders what her one-year-old son Matías will think once he’s old enough to understand.

“I don’t know what to expect,” she says, breaking into an incredulous laugh. “But I know that as urban artists we have great power in our hands.

“Our message reaches even those who would rather ignore it. We’re out there in the streets, so they are going to see us – and our images will stick in their subconscious,” she adds firmly. “That’s our big responsibility.”

This article appears in Huck 59 – The Game Changer Issue. Buy it in the Huck Shop or subscribe to make sure you never miss another issue.

Latest on Huck

In the ’60s and ’70s, Greenwich Village was the musical heart of New York

Talkin’ Greenwich Village — Author David Browne’s new book takes readers into the neighbourhood’s creative heyday, where a generation of artists and poets including Bob Dylan, Billie Holliday and Dave Van Ronk cut their teeth.

Written by: Cyna Mirzai

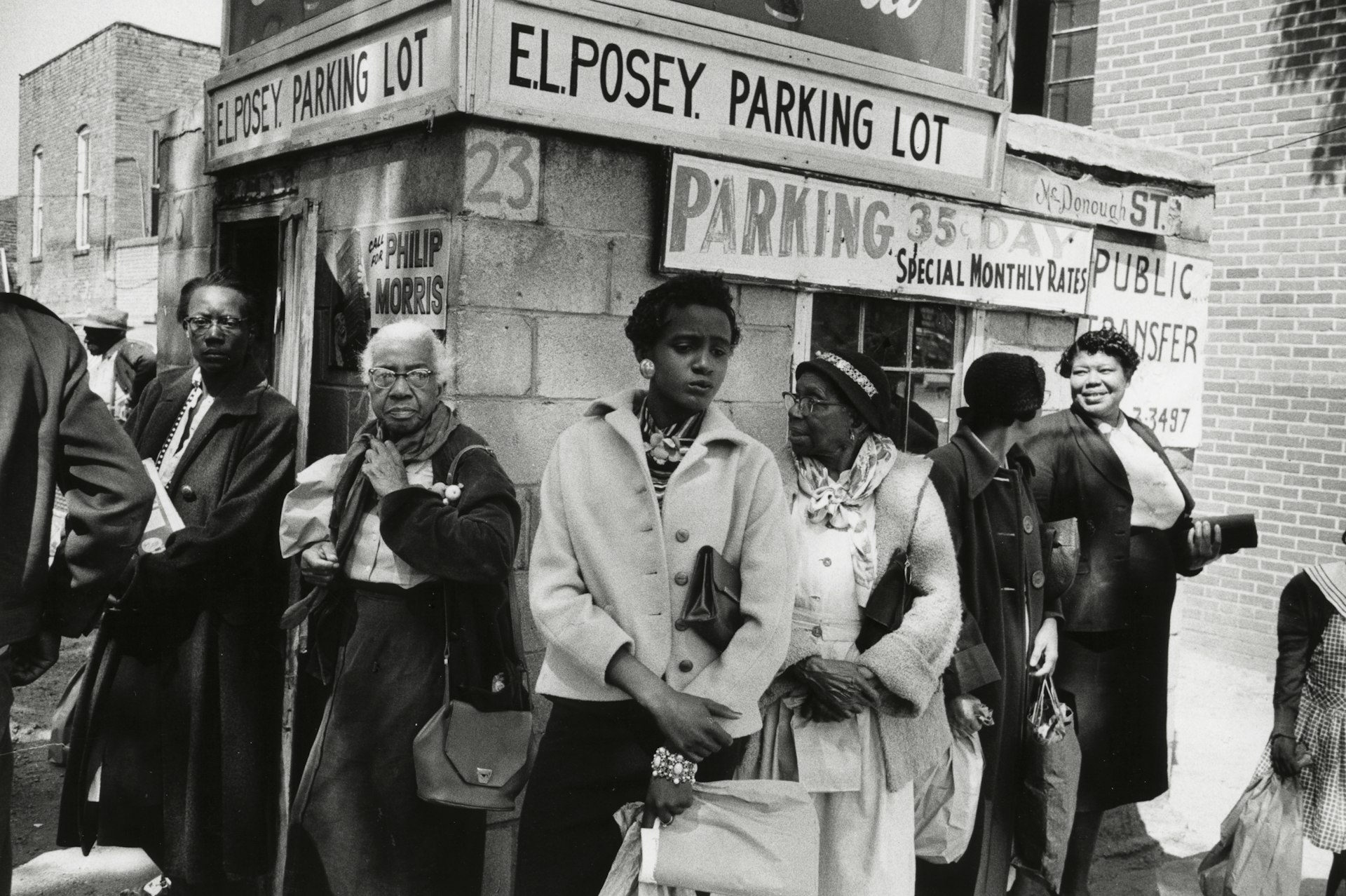

How Labour Activism changed the landscape of post-war USA

American Job — A new exhibition revisits over 70 years of working class solidarity and struggle, its radical legacy, and the central role of photography throughout.

Written by: Miss Rosen

Analogue Appreciation: Emma-Jean Thackray

Weirdo — In an ever more digital, online world, we ask our favourite artists about their most cherished pieces of physical culture. Today, multi-instrumentalist and Brownswood affiliate Emma-Jean Thackray.

Written by: Emma-Jean Thackray

Meet the shop cats of Hong Kong’s Sheung Wan district

Feline good — Traditionally adopted to keep away rats from expensive produce, the feline guardians have become part of the central neighbourhood’s fabric. Erica’s online series captures the local celebrities.

Written by: Isaac Muk

How trans rights activism and sex workers’ solidarity emerged in the ’70s and ’80s

Shoulder to Shoulder — In this extract from writer Jake Hall’s new book, which deep dives into the history of queer activism and coalition, they explore how anti-TERF and anti-SWERF campaigning developed from the same cloth.

Written by: Jake Hall

A behind the scenes look at the atomic wedgie community

Stretched out — Benjamin Fredrickson’s new project and photobook ‘Wedgies’ queers a time-old bullying act by exploring its erotic, extreme potential.

Written by: Isaac Muk