The Firestarters: meet the photographers who captured punk

- Text by Jack Richardson

- Photography by See captions.

- Illustrations by Feature image: Anita Corbin.

The Photographers’ Gallery is not a ragged building. Large windows run straight up and down; inside, the decor is clean, cool and modern with black tile floors and light wooden tabletops. Not, in other words, the most punk venue in London.

And yet gathered in the café, chatting amiably, are figures from just about every British subculture from the 1970s. The Stranglers are playing over the sound system. Amid the crowd of (mostly) normally-dressed people are figures with striking home-made tattoos, parents with Mod-ish children, women with skinhead buzz-cuts.

This is the opening night of the Punk Weekender, the latest in a string of events by Punk London designed to celebrate the subculture’s 40th anniversary.

Gavin Watson: ‘Skinhead Boys, High Wycombe’. 1980

The weekender itself runs from June 23-26, promising a catalogue of talks, a performance by The Raincoats and an exhibition of photographs by Derek Ridgers, Anita Corbin, Janette Beckman, Owen Harvey and Shirley Baker.

In a quiet corner, away from the crowd, Derek Ridgers recounts his experiences. A tall man with thick glasses and an iron-grey ponytail, he has less the look of a punk as that of a hardened photographer who has seen his fair share of change.

“I was never a punk,” he says, when I ask him how he feels about the formal setting for a body of work documenting anti-establishment groups. “I don’t feel ownership of any part of the punk history. I was just there recording it and would like people to see it.”

Derek Ridgers:

‘Soho.’ 1978.

Since his first show, Some Punk Portraits, at the ICA in 1978, Derek has worked hard to share the subculture’s story. The only backlash he’s experienced has been not from punks but from comments on the Guardian.

“I didn’t read most of it after the first couple of pages because it seemed I couldn’t do right by either of them,” he says, chuckling.

And it wasn’t just punks that piqued Derek’s interest. Much of his work has focused on fringe culture figures from all walks of life – including skinheads (the source of the Guardian comments), prostitutes and rent boys.

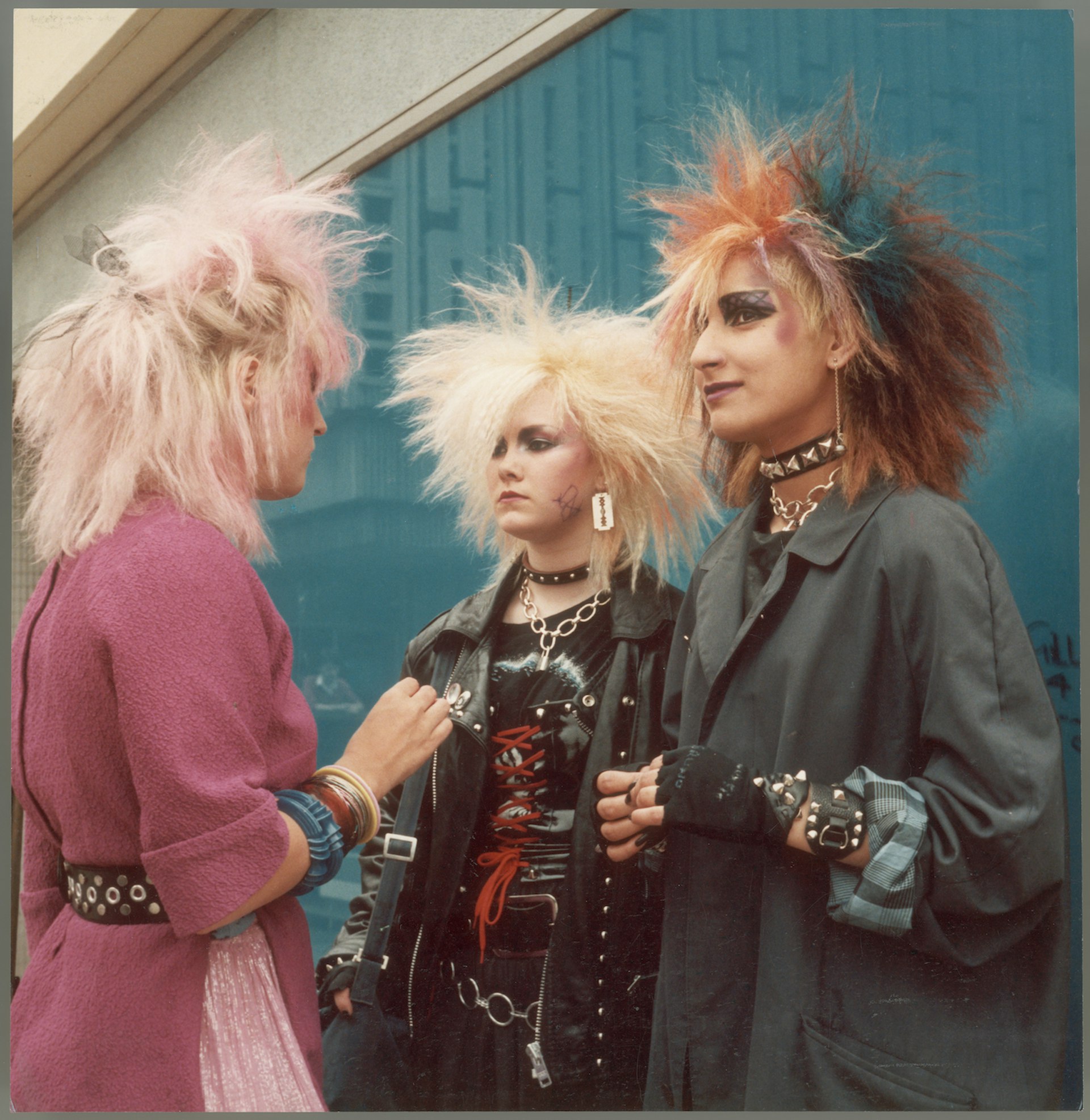

Anita Corbin:

‘Blitz Kids at The Blitz Club’, December 1980. From the series Visible Girls.

Over time, he has come to realise that much of what he was doing was driven by a vicarious curiosity. “I suppose I felt I was an only child and my parents weren’t particularly sociable,” he says. “I felt like I was looking through a window into a slightly more interesting world.”

That world has, of course, changed considerably in the last forty years. And the greatest trigger, in Derek’s view, is something undeniably millennial.

“The biggest [change] really is social media. I think nothing has a chance to gestate out of the public eye, so it can’t really grow and evolve with its own time. It’s either got to be born and be perfect, or it gets destroyed by online derision.”

Shirley Baker:

‘Two punks drinking cider, Stockport.’ 1983.

But for punk, it’s also been something of a boon. “Punk has gone global,” he tells me. “There are Chinese punks, lost punks in East LA and South Central, and every one of them has got their own idea of what punk is.”

Derek was in many ways an outsider, but Anita Corbin, known for her project Visible Girls, wasn’t afraid to get stuck in. “As Visible Girls developed I realised it was about friendships, and the strength of having two young women together who might have been friends, or sisters, or lovers, and the fact that they had a relationship,” Anita says.

“Then I came in as the third point of the triangle, as it were. It really sort of made the point of who I was, as well, and how I was trying to find my identity. I was more or less the same age, so it was a collaborative affair. It wasn’t a quick snapshot in the street.”

Gavin Watson:

‘Neville and Eldridge, High Wycombe.’ 1980

Anita experienced the 1980s punk scene as a young photographer in her twenties; today her short black hair is streaked with blue. As we talk, she is approached repeatedly by previous subjects, now friends, eager to catch up and discuss the photos.

One of them, Di – whom Anita calls “the only punk in the show” – can be seen with her friend Shelley in a key photograph from the exhibition.

From her vantage point, female rebellion stuck out as something worth recording, not least because previous photography “had always been around the boys and violence”. The women she was surrounded by were breaking all the expectations of how women should dress, behave and be.

Anita Corbin:

‘Karyn and Sarah, British Museum’. March 1981. From the series Visible Girls.

Now that four decades have passed, Di can’t help but be nostalgic. “Wherever you went, you would talk to the punks,” she says of her days and nights out.

“I can’t imagine that today people would talk to each other just because they look similar. It was fresh; it was alive; it was new; it was exciting. I think you don’t have that anymore. Now it’s something different but, 40 years on, it doesn’t have that rush. Maybe it’s just because I’m 40 years older!”

As we gear up to leave, we strike up conversation with a man dressed all in black, with long hair and a homemade Adam Ant tattoo fading on his arm. This is Matt, an IT Manager for a small school. “Now I’ve become the system… but I’m working from within to bring it down,” he says with a grin. “After all, that’s really what punk’s all about.”

Punk Weekender runs at the Photographers’ Gallery until Sunday, June 26.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.

Latest on Huck

This erotic zine dismantles LGBTQ+ respectability politics

Zine Scene — Created by Megan Wallace and Jack Rowe, PULP is a new print publication that embraces the diverse and messy, yet pleasurable multitudes that sex and desire can take.

Written by: Isaac Muk

As Tbilisi’s famed nightclubs reawaken, a murky future awaits

Spaces Between the Beats — Since Georgia’s ruling party suspended plans for EU accession, protests have continued in the capital, with nightclubs shutting in solidarity. Victor Swezey reported on their New Year’s Eve reopening, finding a mix of anxiety, catharsis and defiance.

Written by: Victor Swezey

Los Angeles is burning: Rick Castro on fleeing his home once again

Braver New World — In 2020, the photographer fled the Bobcat Fire in San Bernardino to his East Hollywood home, sparking the inspiration for an unsettling photo series. Now, while preparing for its exhibition, he has had to leave once again, returning to the mountains.

Written by: Miss Rosen

Ghais Guevara: “Rap is a pinnacle of our culture”

What Made Me — In our new series, we ask artists and rebels about the forces and experiences that have shaped who they are. First up, Philadelphian rap experimentalist Ghais Guevara.

Written by: Ghais Guevara

Gaza Biennale comes to London in ICA protest

Art and action — The global project, which presents the work of over 60 Palestinian artists, will be on view outside the art institution in protest of an exhibition funded by Bloomberg Philanthropies.

Written by: Cyna Mirzai

Ragnar Axelsson’s thawing vision of Arctic life

At the Edge of the World — For over four decades, the Icelandic photographer has been journeying to the tip of the earth and documenting its communities. A new exhibition dives into his archive.

Written by: Cyna Mirzai