How I uncovered my family’s Nigerian bread empire

- Text by Chanté Joseph

- Photography by Oladimeji Odunsi

My grandfather was warm yet mysterious, in the way that all ethnic grandparents are when they carry whole lives full of secrets and stories in their weighty memories. Like many of our Caribbean elders, he was incredibly quiet about life before migrating to the UK. He was Jamaican and I was British, and he would lovingly remind me at every chance he got.

It wasn’t so much a resistance to divulging his life story; he would always show us themed slideshows of his trips to Jamaica beaming with pride. It was more about acknowledging previous hardships and wanting a better future. However, there was always an air of mystery around his past, that came to light as so many things do – during a tragedy.

After my grandfather’s sudden passing, my great-grandmother revealed that the tall and softly spoken man that was my great-grandfather wasn’t actually my great-grandfather at all. It was instead someone called Lloyd Algernon Shackleford – a Jamaican man with bakeries in Nigeria and Ghana. It was from that moment, my dad and I began to delve into the history of our family, and what we discovered provided a small glimpse into the alliances and affinities that exist between Black people globally.

The story of West Indians in Nigeria is a complex one that dates back to the mid-nineteenth century. In 1872, there were 68 West Indians living in Lagos, and by 1921, there were 194 due to workers coming over to build the railways. Many West Indians did not integrate with native Nigerians but instead found community in other “non-native foreigners”. These included the Saro people, freed slaves who were taken to Sierra Leone by the British Navy and educated as missionaries, and the Amaro, freed Afro-Brazillian slaves who settled in Nigeria.

It wasn’t always a smooth return for the displaced diaspora, with many English-speaking returnees internalising damaging ideas about Africans from their colonial masters. These differences were institutionalised by the Saro people, who acted as middlemen between the colonial officials and indigenous Nigerians. A growing elite class was forming.

Over time, as anti-colonialism sentiments brewed and people grew acutely aware of the false divides, there was a turning point, where some freed slaves denounced their European socialisation and made a concerted effort to reconnect with their roots.

Michael Shackleford (the writer’s grandfather)

My great-great-grandfather, Amos Shackleford, was enamoured by Nigeria. He was born on December 12, 1887, in the Maroons – free communities of Africans who’d escaped from slavery and resided in the mountains of Charles Town, Jamaica. He started out working as an agent for Government Railways in Jamaica, but soon applied for a similar job in Nigeria, for a very insignificant salary difference of £32.

Shackleford had intentions bigger than simply moving for work. The continent had an undeniable pull for him from childhood, that was thought to stem from his Maroon roots and later solidified by his interests in the teachings of Marcus Garvey, who created a ‘Back to Africa’ movement in the United States.

In her paper, A Jamaican Export To Nigeria! The Life Of Amos Stanley Wynter Shackleford, Rina Okonkwo recounts him waxing lyrical to Nigerians he’d met, saying that he’d returned to Africa “to become one of the people of his ancestral home country and [to] take part in her ‘revolution’ to reassert Negro independence and dignity”.

While in Nigeria, he didn’t shy away from politics. He had strongly-held beliefs in anti-colonialism, but disapproval of these sentiments by colonial authorities meant there were limits to expressing them. Despite this, Nigeria had the most developed and active Garveyite groups in West Africa.

The Lagos branch of the United Negro Improvement Association was founded by Shackleford in 1920, and was heavily populated by West Indians. The group were much more business-oriented than politically inclined. Shackleford later helped Herbert Macaulay set up the Nigerian National Democratic Party, where he served as the party’s vice president and was an ardent supporter of Nigeria’s independence.

During the 1920s depression, after training as an accountant, Shackleford left the world of business to pursue a new career in baking. His bread empire spread across Nigeria and Ghana, to the extent that the word ‘Shackleford’ was synonymous with ‘bread’ for non-English speaking Lagosians. Though bread was first introduced to Nigeria through the Brazilians, it was advancements made by West Indians that solidified its place as a staple cuisine.

Amos Shackleford

Shackleford introduced mechanised baking through the famous dough brake machine and formed an organised independent vendor system that allowed for the wide-reaching distribution of bread. His bread would regularly be delivered to Agege in Lagos, until services were disrupted by independence.

Soon after, Alhaji Ayokunnu set up his own bakery, naming it ‘Agege’. Shackleford’s legacy as Nigeria’s ‘Bread King’ is immortalised by the Wheatbaker Hotel in Ikoyi Lagos which used to be his home. His request after passing was that he be laid to rest in Lagos, and his death brought together those young and old across all social classes.

Shackleford is just one story of the many West Indians that moved to Africa to learn and reconnect with their heritage. He is a reminder to me that my politics and belief in black liberation must be an international one, beyond my own material reality in the west.

The diaspora is wonderfully different, and we should appreciate that it is important to interrogate our ideas of each other, as colonialism tried to wedge barriers between us. As Diane Abbott once tweeted: “White people love playing ‘divide & rule’ We should not play their game”.

Find out more about Black History Month 2020 by visiting their official website.

Follow Chanté Joseph on Twitter.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.

Latest on Huck

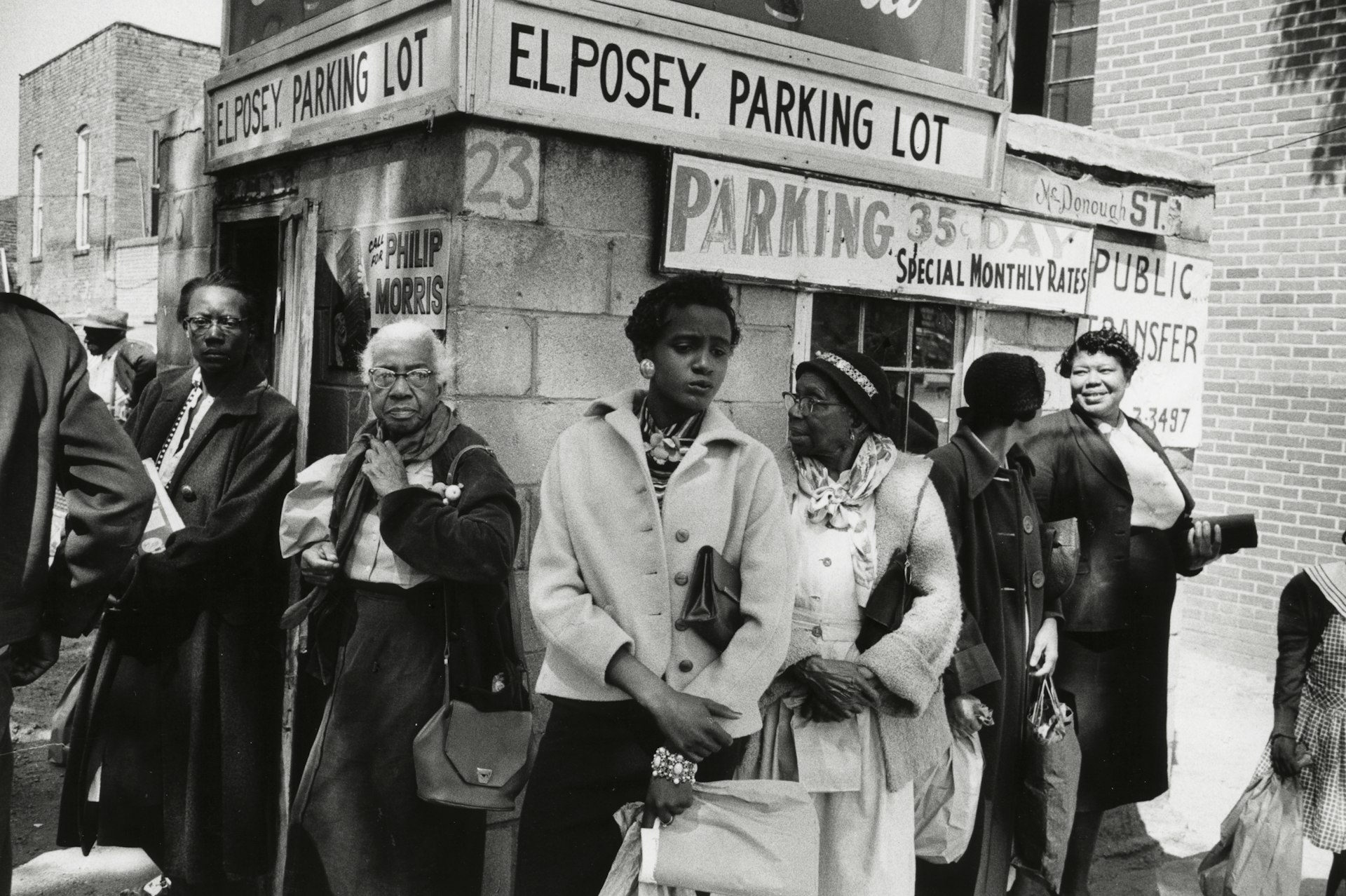

How Labour Activism changed the landscape of post-war USA

American Job — A new exhibition revisits over 70 years of working class solidarity and struggle, its radical legacy, and the central role of photography throughout.

Written by: Miss Rosen

Analogue Appreciation: Emma-Jean Thackray

Weirdo — In an ever more digital, online world, we ask our favourite artists about their most cherished pieces of physical culture. Today, multi-instrumentalist and Brownswood affiliate Emma-Jean Thackray.

Written by: Emma-Jean Thackray

Meet the shop cats of Hong Kong’s Sheung Wan district

Feline good — Traditionally adopted to keep away rats from expensive produce, the feline guardians have become part of the central neighbourhood’s fabric. Erica’s online series captures the local celebrities.

Written by: Isaac Muk

How trans rights activism and sex workers’ solidarity emerged in the ’70s and ’80s

Shoulder to Shoulder — In this extract from writer Jake Hall’s new book, which deep dives into the history of queer activism and coalition, they explore how anti-TERF and anti-SWERF campaigning developed from the same cloth.

Written by: Jake Hall

A behind the scenes look at the atomic wedgie community

Stretched out — Benjamin Fredrickson’s new project and photobook ‘Wedgies’ queers a time-old bullying act by exploring its erotic, extreme potential.

Written by: Isaac Muk

“Welcome to the Useless Class”: Ewan Morrison in conversation with Irvine Welsh

For Emma — Ahead of the Scottish author’s new novel, he sat down with Irvine Welsh for an in-depth discussion of its dystopic themes, and the upcoming AI “tsunami”.

Written by: Irvine Welsh