How Manchester’s Northern Quarter lost its soul

- Text by Andrea Sandor

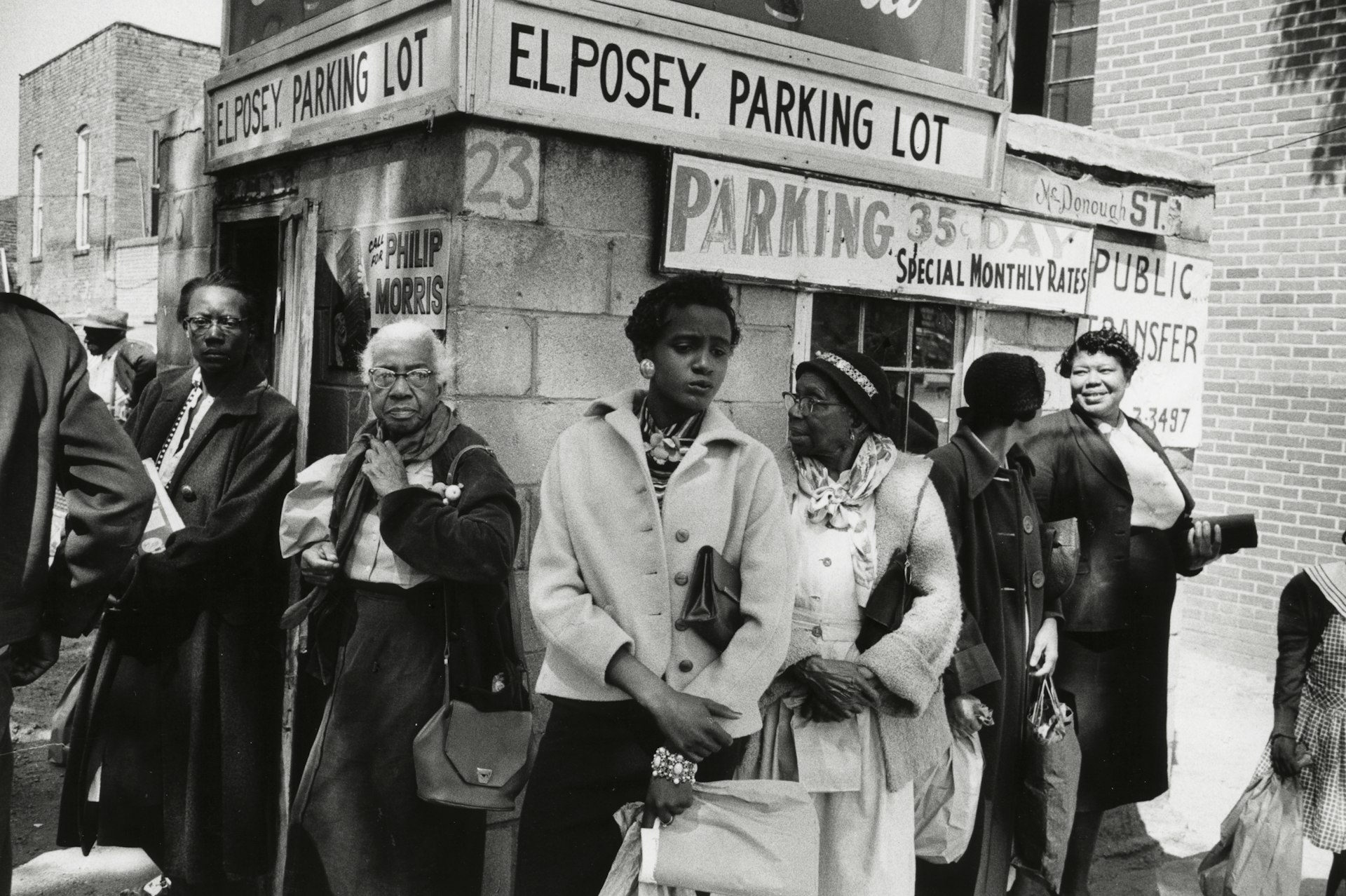

- Photography by Theo McInnes

“The Northern Quarter needs a spiritual kick up the ass,” says architect and academic Dominic Sagar. We’re sitting together in his office at the Manchester School of Architecture (MSA). Clippings of historic buildings are tacked in a mural above his desk, which is cluttered with sketches and architectural plans.

Dominic didn’t plan on becoming an academic, but by 2008 he needed a change. He’d been a key player in the regeneration of Manchester’s Northern Quarter, with his architectural practice helping to restore nearly 150 historic buildings in the neighbourhood.

But rather than become a zone for experimentation and an incubator for small businesses as he had envisioned, Dominic felt the Northern Quarter was en route to full blown gentrification – and he worried that he’d unwittingly been part of that process.

“I’m fuming about what’s happening to my city,” he says, “Where are the new places to play – the cheap creative places to establish independent businesses? We were a group of caring people who had real love for the area – but, like many other places, the Northern Quarter became a victim of its own success.”

The beginning

The Northern Quarter, which lies in the north east of the city centre, is classified by Google as Manchester’s ‘indie’ heartland. It’s home to artist studios, alternative music venues, record stores, and vintage clothing shops.

But in recent years, the area has become increasingly overrun with bars and restaurants, many of which appear to be independent but are actually owned by a small handful of ‘mini empires’. It has also become a party zone and hotspot for short-term lets, characterised by out-of-towners throwing all-night parties and failing to follow waste management rules.

Now big property developers have moved in, signaling what academics have identified as the final stage of gentrification. The ‘luxury’ flats being built don’t provide mixed-income housing, with one developer telling me openly the scheme won’t be marketed to locals because they won’t be able to afford it. With property prices pushed up further, the area will become a ‘ghetto for the well off’. So how did it come to this?

Around 40 years ago, Manchester fell from its post as the world capital of the textile industry into a depressed backwater. The Northern Quarter, which had been at the centre of the industrial revolution, had lost much of its commerce. The bustling Smithfield Market, that covered over four acres at its zenith in 1897, shut in 1972. Around the same time, the nearby Arndale shopping mall opened, swallowing up the remaining quirky specialist shops in the area, leaving many buildings derelict.

The area slipped into further neglect and became reputed as a sketchy no-go zone. Then, in the early ’80s, Afflecks Palace opened its doors. A vibrant, colourful indoor maze-like bazaar, young people met here (and still do) to buy records, tie-dye t-shirts, and flared jeans. Afflecks became a mecca for the counterculture taking the city by storm. The region’s dire state had given rise to the punk scene, as well as bands such as Joy Division, the Smiths, and the Stone Roses.

Dominic and his peers came of age in this exciting, rebellious era and were infected with its non-conformity and do-it-yourself mentality. They were also influenced by the ethos behind Afflecks, which was to provide a supportive environment for businesses starting out. Afflecks charged affordable rents on a week-to-week basis, rather than offer long-term contracts.

As Dominic and his contemporaries left school, they carried this ethos forward, setting up small businesses of their own in the neighbourhood. The Northern Quarter’s derelict buildings and deserted mills provided the perfect playground for the new settlers.

“[We were] early urban explorers,” Dominic has written, “drifting around this abandoned area, the city almost at its majestic best in its decay.” He describes how this “ragtag bag” of artists, musicians, charities, and small businesses who moved in kitted out their offices with items they found in the empty buildings: furniture, fittings, slabs of slate, and pieces of rubber.

Dominic set up an architectural practice with Neil Stevenson on Tib Street. They lovingly restored the tatty Victorian building, and Dominic also opened a shop – Yum Yum – in the basement. On visiting, Mick Middles of the Manchester Evening News wrote, “It has been said that Yum Yum is a shop specialising in soul music and cheese graters… Where else in Manchester could you stumble to decide whether to opt for the tea infuser, the ’60s Brazil football shirt or the Caroline Auty sculpted vase?”

Although the area was desolate, it wasn’t completely deserted. Textile wholesalers were still there – most of whom have since been priced out – as were residents living on the Smithfield social housing estate built in the late ’70s.

The new settlers befriended the local traders and residents and soon discovered, in Dominic’s words, “an underlying burning resentment to how the area had become neglected and abandoned.” Eventually, “a head of steam built up and the first informal meeting was organised.”

In time, the group formalised themselves into the Northern Quarter Association in 1993 and appointed Liam Curtin as artist-in-residence. Apart from instigating public art works, Curtin and NQA managed to get funding from the Council and drew up a five year plan in 1994/5 that laid out a vision for improving the built environment and developing the neighbourhood into a ‘creative quarter’ with tangible short, medium and long-term goals.

The plan provided strategy and much needed guidance for the Council, initiating a number of developments. Regeneration company Urban Splash renovated the Smithfield Building, transforming the abandoned department store into flats. Sagar Stevenson Architects began listing and renovating numerous historic buildings, ensuring their character was preserved. Public art projects were also carried out, crucial for the area’s growing reputation as a bohemian hub.

“It was a labour of love,” Dominic explains. “At the time we didn’t really know what we were doing, we were just doing it, a la the situationists’s punk mantra ‘Just do it and see what happens.’”

The group achieved their five-year plan around the turn of the century. They woke up to the reality that not only had they exhausted their personal resources – financial and emotional – the area’s success was moving in a direction they hadn’t intended.

“I basically had a nervous breakdown,” Dominic says. NQA’s motivation for developing the area had been to improve it, but he felt newcomers on the scene mainly wanted to profit from it.

“Initially, it was everybody coming together – locals, residents, businesses – saying ‘What can we do to help?’ It was spiritual, loving, and caring. Then people started coming along, including the Council, and it kind of changed to, ‘What can we get out of it?’”

Gentrification takes off

NQA are now a footnote in the history of the Northern Quarter. The group have long since disbanded and many of its members have moved away, disillusioned with the neighbourhood and how it’s developed.

Whereas NQA and the owners of Afflecks Palace had wanted the area to be an incubator for businesses – in which rents and overheads were controlled and conditions flexible – unregulated capital instead saw the winners as those making the biggest buck most quickly.

In the early ’00s, at the time NQA successfully finished delivering their plan, budding restaurateurs began opening bars and restaurants in the area in a similar quirky vibe to the Mancunian counterculture. Once a venue was up and running, turning a profit, they bought up another cheap, vacant property nearby and opened another one. This is how many of the eateries and drinking holes in the area became owned by a small handful of individuals – even though it looks like they’re all independent.

It’s difficult to begrudge these restaurateurs for making a success of opportunities before them – and these mini-chains aren’t the global chains of the high street. And yet it’s not what NQA had in mind. The Northern Quarter isn’t a truly independent place anymore, but a premium location for those with significant capital, whether they’re the area’s so-called ‘mini-empires’, or new high rollers on the scene.

Within the past 18 months this has ramped up, with small arts and community organisations pushed out when rents were put up 30 per cent – 40 per cent. Big property developers are now hungrily moving into the area, building ‘luxury’ flats for sale to overseas investors.

The Northern Quarter has become a tourist magnet, Airbnb hotspot, and party district. At the same time, due to austerity and financialisation of the housing market, the condition of the area is miserable. Bins overflow, remaining derelict buildings crumble, while anti-social behaviour and drug use often take place in broad daylight.

The Council has left the area to develop organically, which was a prudent approach at a time when there were individuals and groups who genuinely cared for the neighbourhood and were given some resources. But these groups are now mostly gone, either priced out or fled from an area that developed into something they didn’t want it to become.

“There are two Northern Quarters”

The Northern Quarter has long been a mixed use space, for residents and for commercial enterprise. Some of those who moved into the Smithfield Estate in the ’70s still live in council housing, while many have bought their homes under Right to Buy. Those who still live there find themselves in an area increasingly out of step with their own lifestyle.

Ian Birtle moved onto the Estate in 1983 and has lived there ever since. Before becoming a loom mechanic at the National Trust’s Quarry Bank Mill, he worked at several mills across the city.

“There are two Northern Quarters,” he tells me. Which one you belong to is defined by which pubs you frequent. He rattles off the pubs that haven’t “gone over” yet, where you can still buy a pint for a reasonable price and where there’s “free and easy” music. The clientele is completely different, he tells me. “You’d think you’d stepped back in time.”

I’m surprised when Ian tells me this, because he suggested we meet at a trendy bar – definitely not an old-timey one. “I just don’t know how people have the money to go out to these places,” he says, in a hushed tone.

It’s the exact same refrain I hear from David, a retired drag queen who once owned Anything Theatrical, a colourful costume shop on Oldham Street. Although retired now, David still makes wigs for queens, including contestants on RuPaul’s Drag Race.

David’s invited me over to his house on the Smithfield Estate, a lovely house with deep red wallpaper and gorgeous antique furniture, bought at auctions for pennies and expertly restored. His main issue with how the area has changed is the same as Ian’s: how can people afford it? “I don’t know how people have the money. What kinds of jobs do these people have?”

The future

The Northern Quarter Association had a vision for an urban future that ultimately didn’t come to pass – at least in part due to the consequences of financial deregulation. It seems like the Northern Quarter’s unique quirky independent character ultimately served the interests of capital, where it was commodified.

And yet David and Ian aren’t ready to say the area’s lost its soul, even if more and more of the pubs they frequent are “going over”. There’s still a mystique around the Northern Quarter, they point out: it’s still home to street art, record shops, used clothing stores, and informal mass skater gatherings. And while many of its characters have since moved on and taken different paths, new personalities have moved in who are also passionate about making the area a good place to live.

The Northern Quarter has a new resident’s forum, fighting tooth and nail for its community. Their most pressing concerns relate to the basics: waste management, drug use, disruptive Airbnb’rs and anti-social behaviour, saving historic buildings from demolition. They’ve had success so far, too; forcing the Council to more proactively manage waste, forcing developer Salboy (owned by Betfred billionaire bookie Fred Done) to return to their plans and save a historic building on a development site, and getting permission to close Stevenson Square to traffic for a night to host a pop-up park (no easy feat).

The forum is led by Tony Cross, a lawyer with thick-rimmed black glasses who rides a Brompton to work and shouts at groups of young visitors to “pick up your mess.” (When they protest they’ve just arrived and haven’t made a mess, he replies, “but you will.”)

Meanwhile, his wife Joanne, secretary of the Forum, strolls around the streets in white billowing garments with their huge boxer, keeping an eye on everything happening in the area. She’s on a first-name basis with many of the area’s regular beggars, and is the first to ask a builder on site what’s happening and why there hasn’t been a public consultation.

While the Forum recognises change is inevitable, they are trying to ensure the Northern Quarter remains a place for creative, young people, with Tony telling me: “The Northern Quarter is many things – litter and the abuse of short-term lets are two examples of what we deal with on a daily basis – but what we are really fighting for is the very soul of the Northern Quarter.”

The Forum has worked with Dominic and his MSA colleagues and students to develop solid plans for the area, which they believe will protect it from becoming a developer’s playground. A new wave of local activism is here.

But is it too late? The Northern Quarter is at a tipping point, and there could be reason to fear that the arrival of developer Salboy sounds the death knell.

And yet in the era of Brexit, Johnson and Trump, it’s exactly visions like those of the NQA that we need to retrieve, when markets need to be regulated and supportive environments for community and small entrepreneurs encouraged. As the neoliberal order teeters and we look towards the future of urban areas, it’s time to retrieve some Northern Quarter soul – something that will perhaps give it, as Dominic says, a spiritual kick up the ass.

Follow Andrea Sandor on Twitter.

See more of Theo McInnes’ work on his official website, or follow him on Instagram.

Latest on Huck

How Labour Activism changed the landscape of post-war USA

American Job — A new exhibition revisits over 70 years of working class solidarity and struggle, its radical legacy, and the central role of photography throughout.

Written by: Miss Rosen

Analogue Appreciation: Emma-Jean Thackray

Weirdo — In an ever more digital, online world, we ask our favourite artists about their most cherished pieces of physical culture. Today, multi-instrumentalist and Brownswood affiliate Emma-Jean Thackray.

Written by: Emma-Jean Thackray

Meet the shop cats of Hong Kong’s Sheung Wan district

Feline good — Traditionally adopted to keep away rats from expensive produce, the feline guardians have become part of the central neighbourhood’s fabric. Erica’s online series captures the local celebrities.

Written by: Isaac Muk

How trans rights activism and sex workers’ solidarity emerged in the ’70s and ’80s

Shoulder to Shoulder — In this extract from writer Jake Hall’s new book, which deep dives into the history of queer activism and coalition, they explore how anti-TERF and anti-SWERF campaigning developed from the same cloth.

Written by: Jake Hall

A behind the scenes look at the atomic wedgie community

Stretched out — Benjamin Fredrickson’s new project and photobook ‘Wedgies’ queers a time-old bullying act by exploring its erotic, extreme potential.

Written by: Isaac Muk

“Welcome to the Useless Class”: Ewan Morrison in conversation with Irvine Welsh

For Emma — Ahead of the Scottish author’s new novel, he sat down with Irvine Welsh for an in-depth discussion of its dystopic themes, and the upcoming AI “tsunami”.

Written by: Irvine Welsh