‘We’re learning by doing’: Inside the Faroe Islands’ new music boom

- Text by Martin Guttridge-Hewitt

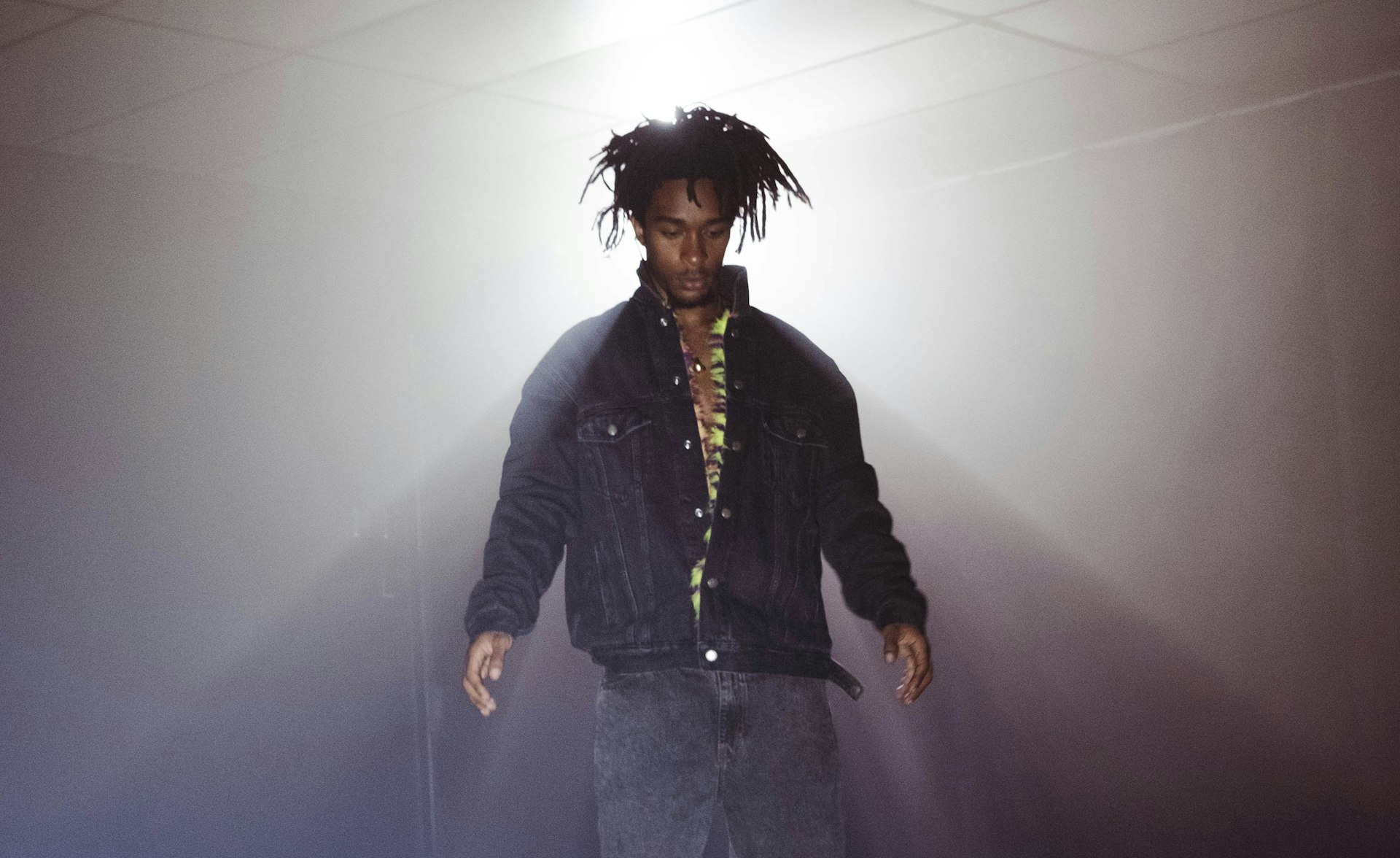

- Photography by Gwenaël Akira Helmsdal Carre

- Illustrations by Marta Parszeniew

Spaces Between the Beats is a series spotlighting music and cultural communities around the world, exploring their stories as they build resilience and find meaning and hope in connection.

In midsummer Tórshavn barely sees nightfall, just a fleeting hour or two of dark before a grey half-light envelops the green-red timber frames and grassy roofs of its buildings. Neither dawn nor midnight, it’s an atmospheric backdrop for what’s happening.

On one of the city’s narrow streets, “queer vegan shitpunks” Joe & The Shitboys are commanding a mosh pit with breakneck songs about hidden prejudice, false enlightenment and double standards in a terminally ill world. Despite quaint first impressions of this toy box town, home to around one-fifth of the 53,000 people living on the Faroe Islands, the scene is apt for the country’s first alternative music showcase, Skrapt – a three-day spotlight on the young talent, ideas and attitudes, reflecting changing tides in a culture often considered to be floating adrift somewhere between Scotland and Iceland.

“We sing about issues a lot of people can relate to, but to us they’re prevailing issues we experience,” says frontman Fríði Djurhuus, AKA Joe. Citing their song ‘Closeted HomoFObe,’ he explains that veiled bigotry prevails within the Faroe Islands, even if its violent crime rate is among the world's lowest. “We also talk about climate change and everybody thinking stopping using plastic bags will save the world when leaders are flying in private jets, destroying everything. That doesn’t mean don’t try, but it’s useful to point out the absurdity.”

Toxic masculinity is another of The Shitboys’ hot topics. With the nation’s leading economic sectors – such as fishing and agriculture – still considered the preserve of men, traditional gender stereotypes pervade, although Joe believes these views are shifting with generations. “In the mountains the men go gather the sheep, maybe shear them, maybe slay them. Whaling too. Every generation cares a little bit less about these things,” Joe explains. “There’s a theory that small communities want to live in harmony even when they are disharmonious. You can have different views but I’m still gonna see you every day in the store. You can go to a family gathering and someone is maybe going to say something problematic. If you confront them, you’re [seen as] the problem. The victims have to mask it. But I think those traditions are changing slowly.”

Sunneva Eysturstein, the co-owner of Sirkus – a cosy wood-clad venue in central Tórshavn – also talks about young Faroese artists pushing against centuries-old expectations through “different music, art, dance and literature.” Skrapt’s co-founder, her intention for the festival was to offer a platform for alternate forms of expression – which ranges from NÖNNE’s dark, spatial R&B, to Ayphin delivering life lessons from his village of Fuglafjørður with razor sharp flow, to the infectious hip hop instrumentals of Ghost Notes, with Eysturstein’s bar hosting the afterparty.

“In Tórshavn you can definitely see things are changing,” says 24-year-old Dania O. Tausen, who moved to the capital before the pandemic from Toftir, a village on the neighbouring island of Eysturoy with a population of around 980. Until a subsea tunnel opened in 2020, it took over an hour to get from Toftir to the capital – accentuating how limited infrastructure has meant isolation even within the country’s small geographic area. “What’s sad is that [change] goes the right way but there’s always a reaction out in the towns,” Tausen continues. “I moved here as I wanted more culture. Where I grew up there was religion and sports. I really wanted to attend concerts and I was interested in poetry, but there was nothing there. Here, I can experience more.”

Initially Tausen didn’t find many poetry readings, so she took things into her own hands and started putting on events where people could read their work or simply come to listen. Our interview takes place after a reading from her debut poetry book, Skál, which touches on faith, reclaiming feminine sexuality from the male gaze and personal growth. “It was important to me there were authors or poets that had released books – but also young people that just love it, so everyone can share,” she says. This act of platforming Faroese voices also extends to her job at Tutl, a record shop in Tórshavn with a label of the same name acting as the leading representative and distributor of Faaroese music worldwide.

Established in 1977 by Danish composer, musician, record executive and Faroe Islands resident Kristian Blak, Tutl’s remit is as broad. Basically: anyone from the islands who wants to put music out. Its back catalogue is a goldmine of work by amateurs and renowned names like Eivør Pálsdóttir. “When I walked [into the shop] I saw this wall of Faroese music – a whole wall! And I didn’t know any of it,” Tausen remembers. “ I was 20-years-old. I’d been living in a bubble of the town and church, so I only knew psalms and The Bible. I spent the next year exploring my own country’s music, then started making my own.”

Tausen writes and sings in Faroese – a trend among many young artists that’s as much about accurate expression as it is nationhood. The islands gained autonomy but not independence from Denmark in 1948, and the relationship is complex. Copenhagen runs the courts and subsidises various sectors, including music. In 2019, the Faroe Music Export (FMX) office was founded to increase global visibility for artists through securing international opportunities, from festivals to studio partners to press agencies.

FMX Head Glenn Larsen relocated to Tórshavn from Norway mid-pandemic. When we meet for a day out exploring breathtaking Faroese landscapes, he modestly half-jokes the job was a case of right time and place – him being an artist manager with longstanding experience in a place where seasoned industry professionals are in short supply. Even so, his desire to make the institution work is clear. “For me, when you find some new music or see a new band, you want to show your friends,” Larsen tells me. “I felt like I’d been handed a whole country to present to the rest of the music industry.”

“It’s a cliché that everyone on the Faroe Islands can do at least five jobs: work in a bank, as a fisherman and as a sound engineer. Musicians are the same. Techno producers playing in a jazz trio, or a covers band member in the symphony orchestra also making death metal.”

This vibrant, experimental Faroese scene has also lured overseas acts. Footwork and ghostly garage producer Lasse Jæger, aka Supervisjón, is a case in point. Following his set at Skrapt, where 140BPM drums thundered beneath choppy samples of soundbites heard during his own mortgage advice meetings, he recounts emigrating from Denmark four years ago and discovering “a shorter path between getting an idea and making it happen, and an even shorter one to someone saying 'come and play this concert” compared to larger countries.

He also speaks of a strong collaborative spirit that's fundamental to the scene. “It’s a cliché that everyone on the Faroe Islands can do at least five jobs: work in a bank, as a fisherman and as a sound engineer,” Jæger laughs. “Musicians are the same. Techno producers playing in a jazz trio, or a covers band member in the symphony orchestra also making death metal.”

Forward-facing techno artist La Leif, hailing from South London, has had a similar experience. “Everyone helps each other out,” she says after her solo performance at Skrapt. “It feels really refreshing, people look after you and I think are more invested in what you’re actually doing.” When we grab a beer she’s joined by Jens L Thomsen – a go-to mixer and engineer for many on the islands, and her partner in the Faroes-born ORKA electronic music project. Both of them recount instances of this collectivist ideology in action, from kit shared between music-making friends to shows booked with 24 hours notice by audience members-turned-promoters.

Later, we find Marianna Winter lowering herself into a deep wooden bathtub of ice cold water at Skrapt’s Sunday evening “extreme chill session.” One of several contemporary Faroese artists to break overseas, her stunning voice and uptempo soul tracks captivated the festival crowd two evenings earlier. Drying off before speaking, she paints a vivid picture of how nationality and self-determination are interlinked with culture.

“It’s important for people to understand the Faroe Islands as our own country. But in many aspects we’re still referred to as Denmark, which is a huge problem,” Winter says. “People are no longer moving from the Faroe Islands because it’s become a cool place to live. It wasn’t a couple of years ago. That’s why all the young people moved to Copenhagen or England. So more are staying and that’s cool, but we have to figure out what we have to offer, and what this country offers us. The Faroese music industry is still far behind the rest of the world, as we are in many factors – like politics.

“Look at gender equality. Women don’t own the rights to their own bodies as we have very strict abortion laws, even though Denmark changed theirs way back,” she continues, citing the ongoing influence of Christianity throughout day-to-day life in the Faroes, from high school to state legislation. A recent tourist guide puts 80% of the population as belonging to the national church.

“I feel you have a lot of responsibility – not just to yourself, but to all the artists around you [...] It's weird, trying to teach each other something while you're still learning, but it probably makes learning easier. It's kind of been like that for Faroese artists: learning by doing.”

The depiction of Faroese communities bound by religious values reinforces assumptions of cultural isolation, but it also frames the passion with which so many talk about breaking free from conventions and being heard on their own terms. It’s a reflection of things moving into a more outward-looking era in which national identity still counts, though it may not look like it once did. Art, it seems, is at the forefront of this change.

“I think we’re seeing a lot more individuality in artists now. There are so many new musicians, and young musicians, in different bands. Before it was often the same musicians playing in all the bands, giving them all a similar sound.” Winter observes, adding that it’s exciting to see writing in Faroese become ‘in’ again. “Seeing music released in Faroese, but aiming internationally, even though there are like 50,000 people who understand the language, is really cool.”

All artists I speak to believe that the success of Faroese artists relies on co-operation, which is something Winter reiterates as our interview comes to a close. “I feel you have a lot of responsibility – not just to yourself, but to all the artists around you.” she says. “We’re all friends, we all collaborate on different projects, we're all musicians in each other's bands – stuff like that. It's weird, trying to teach each other something while you're still learning, but it probably makes learning easier. It's kind of been like that for Faroese artists: learning by doing.”

The need to share experience, knowledge and platforms isn’t just an ideological one across the Faroe Islands – it’s a practical necessity. It feels obligatory; compensation for a notable absence of music industry infrastructure and the sense of being physically removed from the world beyond a North Atlantic often shrouded in thick fog. Ironically, it’s these limitations that may well have created the perfect conditions for the enviable scene today: a trove of talent, void of cynicism, harnessing the true spirit of DIY.

All photos by Gwenaël Akira Helmsdal Carre.

Follow Martin on Twitter.

Latest on Huck

Los Angeles is burning: Rick Castro on fleeing his home once again

Braver New World — In 2020, the photographer fled the Bobcat Fire in San Bernardino to his East Hollywood home, sparking the inspiration for an unsettling photo series. Now, while preparing for its exhibition, he has had to leave once again, returning to the mountains.

Written by: Miss Rosen

Ghais Guevara: “Rap is a pinnacle of our culture”

What Made Me — In our new series, we ask artists and rebels about the forces and experiences that have shaped who they are. First up, Philadelphian rap experimentalist Ghais Guevara.

Written by: Ghais Guevara

Gaza Biennale comes to London in ICA protest

Art and action — The global project, which presents the work of over 60 Palestinian artists, will be on view outside the art institution in protest of an exhibition funded by Bloomberg Philanthropies.

Written by: Cyna Mirzai

Ragnar Axelsson’s thawing vision of Arctic life

At the Edge of the World — For over four decades, the Icelandic photographer has been journeying to the tip of the earth and documenting its communities. A new exhibition dives into his archive.

Written by: Cyna Mirzai

ATMs & lion dens: What happens to Christmas trees after the holiday season?

O Tannenbaum — Nikita Teryoshin’s new photobook explores the surreal places that the festive centrepieces find themselves in around Berlin, while winking to the absurdity of capitalism.

Written by: Isaac Muk

Resale tickets in UK to face price cap in touting crackdown

The move, announced today by the British government, will apply across sport, music and the wider live events industry.

Written by: Isaac Muk