Kai Fusayoshi reflects on a life shooting the streets of Kyoto

- Text by Kai Fusayoshi (as told to Marigold Warner)

- Photography by Kai Fusayoshi

In January 2015, a tragic fire burnt through the Honyarado, a cafe I owned and managed for 43 years, along with my life’s work – my photographic archive. The fire destroyed two million negatives, thousands of prints, and a huge collection of photobooks, along with the treasured cafe, which I established in 1972 with a group of writers, musicians, and activists from the anti-war movement.

I lost so many fantastic images and only ten percent of my archive survived. This month, I displayed a portion of what remained as part of the Kyotographie photo festival by the banks of the Kamo River in Demachi, Kyoto which brought back good memories as it was on the streets of Demachi that I first became a photographer.

I was born in 1950 in Ōita prefecture, on the island of Kyushu in southern Japan. My five siblings and I were raised in a small village of 30 families, on a farm with thousands of chickens and a herd of goats. I was a restless child, I played a lot of sports, including baseball, athletics, and judo, but I hated studying. At home, I used to fool around, attempting to shoot chickens with an air-gun. In an effort to distract me, my older sister gave me a camera. I took my first photographs when I was 11 years old — mostly of my friends, and the chickens — but I didn’t take the medium seriously until much later.

Photographer and wife of W. Eugene Smith, Aileen Mioko Smith (left), attends a rice

cake making competition at the Honyarado, 1978

In 1968, I moved to Kyoto to study Political Science at Doshisha University, but the fees were incredibly expensive, and I was disappointed with the mass-produced education style so I dropped out before finishing my first year. After that, I took up various part-time jobs, squatting in disused student dorms, and attending many student protests, which were erupting across the country at the time before joining Beheiren, an anti-war movement against Japan’s involvement in the Vietnam War. I would go on to spend half a year working as a carpenter in Iwakuni, a city 400km south of Kyoto, where the US stationed their marines helping to build temporary housing for military deserters and working in a cafe called ‘Hobbit’, which became a famous hub for the anti-war movement.

I was a terrible carpenter, but I felt inspired by the counter-cultural ethos of the cafe. Back in Kyoto, I got together with a group of friends from the anti-war movement — poets, musicians, teachers, and artists from all over Japan — and we decided to set up our own in Kyoto. Honyarado opened in 1971, in a two-story wooden house near Doshisha University. Serving cheap meals and strong coffee, it quickly became a hangout for local students, artists, and activists. We hosted poetry readings and live music events, by incredible Japanese artists like jazz singer Maki Asakawa, and popular poet Shuntaro Tanigawa. We also welcomed international guests who stopped by during their visits to Japan, including the Beat Generation’s Allen Ginsberg, and American writer Gary Snyder.

By then, the anti-war movement of the 1960s was waning, and public opinion had turned against us, along with a growing tendency for dissident groups to be labeled ‘extremist’. That was when I started to pick up photography again. From 1974, I extensively documented the Demachi area, photographing children playing on the riverbank, cats lounging across cobbled streets, and, of course, customers who visited our cafe.

Children trying each others ice cream, 1976

A young boy at the market, 1979

Philosopher Shunsuke Tsurumi (middle) and a former American deserter returning to

the Honyarado (right), 1992

I loved documenting Kyoto, but I was criticised for wasting my time. In 1977, I decided to commit myself to the cafe and announced a departure from photography. To commemorate the shift, I published my first photobook, Kyoto Demachi, and held a series of outdoor exhibitions where I pasted prints directly onto the city’s stone walls. If people could find themselves in the images, they were free to take them home. I must have exhibited around 15,000 photographs in total. Shortly afterward, my work was picked up by Kyoto’s largest daily newspaper. I didn’t end up taking a break after all, and since then, I’ve published over 40 photobooks.

In 1985, I opened a new bar called Hachinomiya, where I still serve drinks every day. I continued to manage Honyarado alongside it, eventually transforming the second floor into a library for my archive. Then, 43 years after its opening, the fire destroyed it all.

It is only when I look back now, five years later, that I realise how depressed I was. Four months after the fire, I fell off my bike and cut my leg. I wasn’t sleeping much, I was drinking every day, and the wound eventually developed a bacterial infection. The doctors said I was facing amputation, or in the worst case, death. I couldn’t believe I survived considering how much I’d been drinking. The photographs I have left represent just a portion of my work, but they remind me of a happy time. It has been a joy to see so many people enjoying the images, and spotting themselves in our shared history.

After the evening rain, 1990

Hide and Seek, 1972

Visit from the Chindon’ya marching band, 1976

Outside the Honyarado, 1975

A policeman looks for himself in a Demachi photo exhibition, 1978

Installation at Kyotographie 2020 ©︎ Takeshi Asano

An exhibition of Kai Fusayoshi’s photography as part of the Kyotographie international photography festival has been extended and will be on display in Kyoto until next summer.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.

Latest on Huck

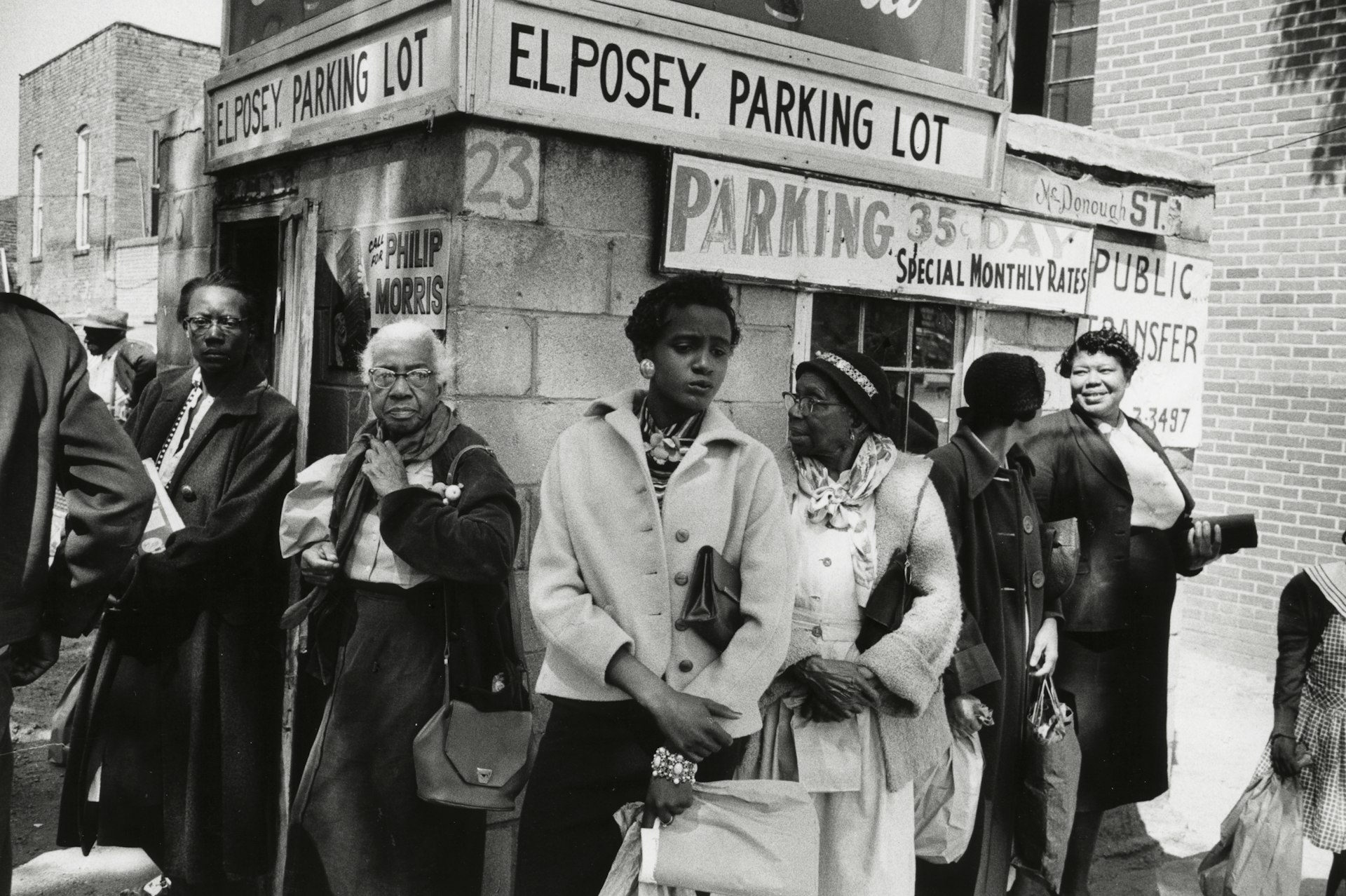

How Labour Activism changed the landscape of post-war USA

American Job — A new exhibition revisits over 70 years of working class solidarity and struggle, its radical legacy, and the central role of photography throughout.

Written by: Miss Rosen

Analogue Appreciation: Emma-Jean Thackray

Weirdo — In an ever more digital, online world, we ask our favourite artists about their most cherished pieces of physical culture. Today, multi-instrumentalist and Brownswood affiliate Emma-Jean Thackray.

Written by: Emma-Jean Thackray

Meet the shop cats of Hong Kong’s Sheung Wan district

Feline good — Traditionally adopted to keep away rats from expensive produce, the feline guardians have become part of the central neighbourhood’s fabric. Erica’s online series captures the local celebrities.

Written by: Isaac Muk

How trans rights activism and sex workers’ solidarity emerged in the ’70s and ’80s

Shoulder to Shoulder — In this extract from writer Jake Hall’s new book, which deep dives into the history of queer activism and coalition, they explore how anti-TERF and anti-SWERF campaigning developed from the same cloth.

Written by: Jake Hall

A behind the scenes look at the atomic wedgie community

Stretched out — Benjamin Fredrickson’s new project and photobook ‘Wedgies’ queers a time-old bullying act by exploring its erotic, extreme potential.

Written by: Isaac Muk

“Welcome to the Useless Class”: Ewan Morrison in conversation with Irvine Welsh

For Emma — Ahead of the Scottish author’s new novel, he sat down with Irvine Welsh for an in-depth discussion of its dystopic themes, and the upcoming AI “tsunami”.

Written by: Irvine Welsh