The London caterers feeding their community

- Text by Huck

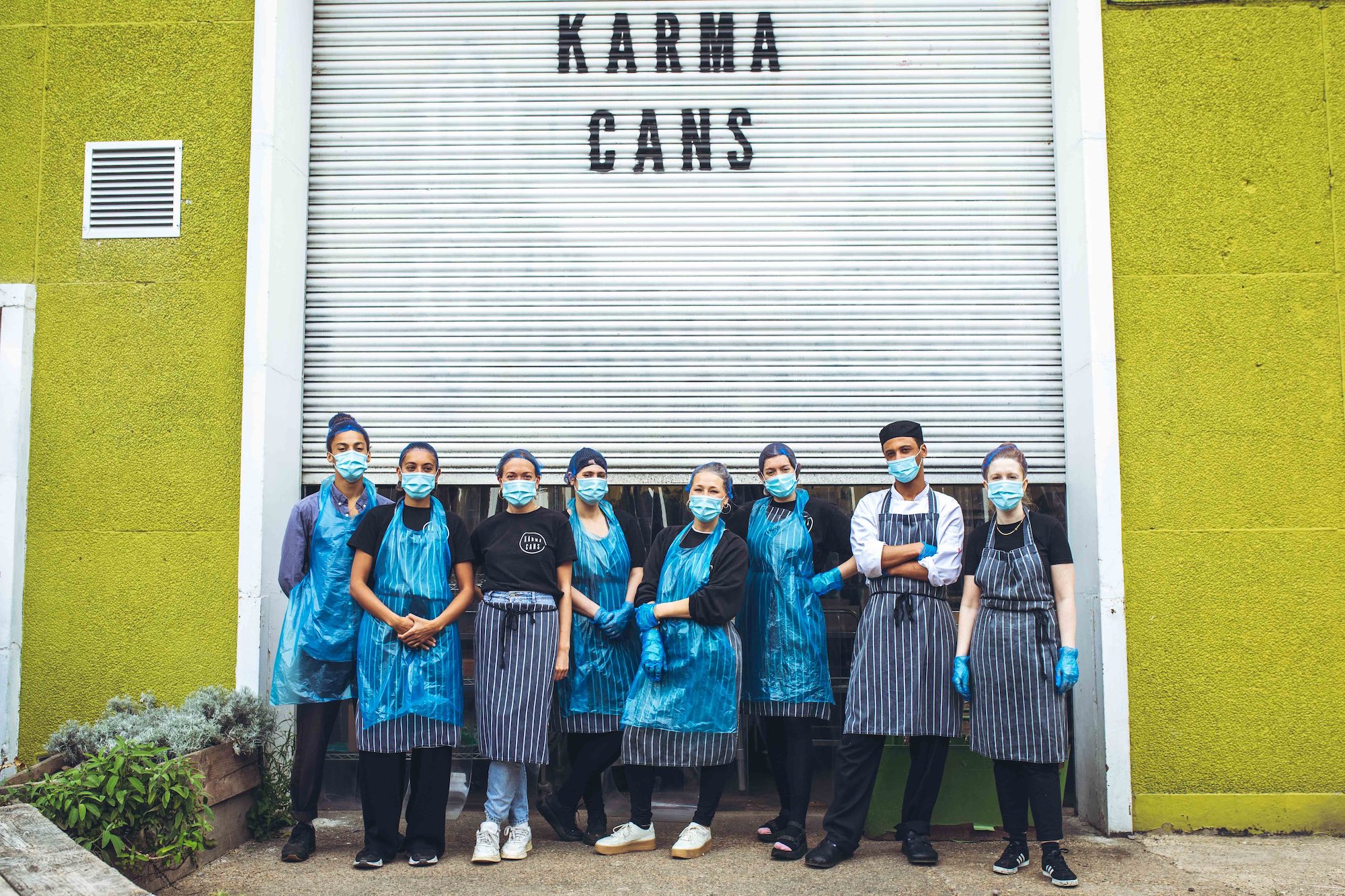

- Photography by Theo McInnes

Six years ago, sisters Gini and Eccie Newton started Karma Cans: a two-woman catering company based in London. In its early days, the pair would do all the cooking and delivery themselves; rocketing around the capital on courier bikes with fresh, seasonal and sustainably-made meals.

Over time, Karma Cans grew into something much bigger. The company – which now has around 15-20 employees – soon began catering for some of London’s biggest businesses, delivering up to 1000 meals a day. Then, the pandemic hit.

Like many companies across the country, Karma Cans’ world was turned upside down. What was once a successful and reliable business model, became instantly irrelevant. “It all happened so quickly,” remembers Gini. “The big clients went first, then the smaller businesses. So, it was really challenging – we’d built this brand for years around corporates, and then suddenly the market just changed overnight and we went from corporate to individual again.”

Despite the grave existential threat, the company managed to pull through. Rather than feeding the big corporations, they slashed their profit margins and shifted their gaze to the community – and in the months since, they’ve worked with the NHS, charities and local councils. In the latest of our new series on Pandemic Innovators, we find out how they did it.

Tell me about how you weathered the start of lockdown. It must have been a huge change – how did you adapt?

We had to adjust really quickly. The safety of the team is really, really important: some of our chefs are living with older people, so we decided to close for two weeks at the very beginning and think about what we wanted to do.

When we did reopen, we did so with a new team. We furloughed our original chefs who couldn’t work and took on new people, because it was an amazing opportunity to help chefs who were recently unemployed. We also managed to get a few different contracts with some hospitals, and started working with the charities Hospitality for Heroes and Meals for the NHS. I think for us it’s not really about the finance, it’s about keeping morale high in the team – by working with NHS charities we were doing something good, and the team felt really happy about it.

How has being a small business helped?

How has being a small business helped?

I think smaller businesses are more adaptable, we’re so used to this kind of hustle because honestly, we don’t have investment, so we don’t have the luxury of a buffer zone. Karma Cans has not always been stable: it nearly failed at the beginning, and mid-way through. But it builds such a resilience into the team, so it means that when trauma hits you act in a very different way to many people who haven’t kind of dealt with that in business before.

What was most markedly different about this direction? What were the biggest challenges?

We had to redesign the menus to suit the NHS: our menus are normally quite elaborate and the costs are very high, so we had to really reduce the ingredients but also keep it tasty. When we were charging £8.50 a head for corporate, with the NHS we had to get it down to £3 a head. So we’ve had to think in an entirely different way.

We also had to remember that doctors and nurses are working such long hours, so the food needs to be filling. We went from corporate catering, which is all about keeping people focused at their desks, to keeping people fuelled on the front line.

What was the feedback from the hospitals?

We were really surprised every time a doctor posted something positive about our food, because for us they’re so busy and the fact that they Googled us or went on our Instagram to find our name was such a surprise. And honestly, that was the reward right there, that feedback.

What’s next for Karma Cans? How do you feel about the future?

Our NHS contracts have ended for now, but we’ve hopefully got a new project with Tower Hamlets to help cater for vulnerable people in the borough. It’s very low budget – around £2 a head – but it’s so worth it. So that’ll be our focus, until we get corporates back. That said, we have decided that our community work has to continue as a part of our business model, because we’ve all really enjoyed doing it. We’re also opening a rooftop residency at Hoxton Docks this summer.

Honestly, when the pandemic first started, it was a complete nightmare. But reflecting on it now, there have been some serious positives. It has been an amazing opportunity to think in a different way; to reexamine our pricing and our food. We just wouldn’t have had the time to really rip the company apart and start again if it wasn’t for the coronavirus. I think we’ll come out of it, hopefully, as a stronger, better business.

Find out more about Karma Cans on their official website.

Do you know any pandemic innovators? If you would like to nominate any other UK companies (or individuals) who have successfully changed their way of working during the coronavirus crisis, get in touch.

See more of Theo McInnes’s work on his official website. You can follow him on Instagram and Twitter.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.

Latest on Huck

Tender, carefree portraits of young Ukrainians before the war

Diary of a Stolen Youth — On the day that a temporary ceasefire is announced, a new series from photographer Nastya Platinova looks back at Kyiv’s bubbling youth culture before Russia’s February 2022 full-scale invasion. It presents a visual window for young people into a possible future, as well as the past.

Written by: Hannah Bentley

Analogue Appreciation: 47SOUL

Dualism — In an ever more digital, online world, we ask our favourite artists about their most cherished pieces of physical culture. Today, it’s Palestinian shamstep pioneers 47SOUL.

Written by: 47SOUL

Meet the hair-raised radicals of Berlin’s noise punk scene

Powertool — In his new zine, George Nebieridze captures moments of loud rage and quiet intimacy of the German capital’s bands, while exploring the intersections between music, community and anti-establishment politics.

Written by: Miss Rosen

Amid tensions in Eastern Europe, young Latvians are reviving their country’s folk rhythms

Spaces Between the Beats — The Baltic nation’s ancient melodies have long been a symbol of resistance, but as Russia’s war with Ukraine rages on, new generations of singers and dancers are taking them to the mainstream.

Written by: Jack Styler

Uwade: “I was determined to transcend popular opinion”

What Made Me — In this series, we ask artists and rebels about the about the forces and experiences that shaped who they are. Today, it’s Nigerian-born, South Carolina-raised indie-soul singer Uwade.

Written by: Uwade

Inside the obscured, closeted habitats of Britain’s exotic pets

“I have a few animals...” — For his new series, photographer Jonty Clark went behind closed doors to meet rare animal owners, finding ethical grey areas and close bonds.

Written by: Hannah Bentley