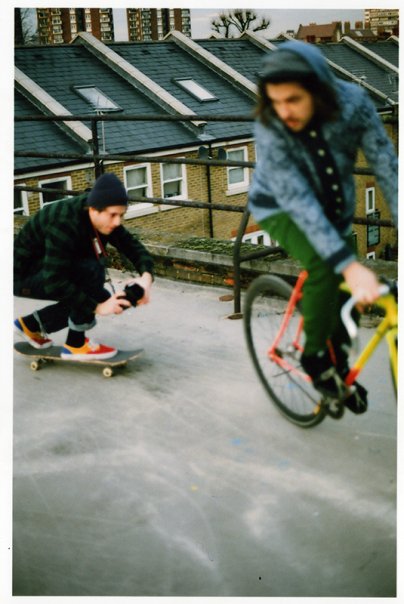

Documenting London squatting culture from the inside

- Text by Alex King

- Photography by Pawel Dziemian

If you believe everything you read in the tabloids, squatters are a dirty bunch of freeloaders who leave a trail of drugs and destruction in their wake. But cast your eyes back through history – particularly through the history of cities in times of crisis – and you’ll see it has often been squats that have birthed creative resurgences and movements of political resistance.

In times and places where the cities around them have been rotting and on the brink of collapse, squats have provided sanctuary for those who would otherwise have nothing. They’ve helped sow the seeds for the new creative lights to emerge from the darkness – think of the empty warehouses on the Lower East Side in the ‘70s and ’80s, when New York was threatened with bankruptcy and pounded by austerity; or Brixton and Hackney in London, where punks and anarchists built a vibrant counterculture to resist the unemployment and despair of Thatcher’s Britain during the 1980s.

Squatting is always political – and the art and creativity of resistance often goes hand in hand.

After graduating from his art master’s in Poland, Pawel Dziemian arrived in London in August 2009 and was introduced to the squatting scene through a friend. With no plans after finishing university and a hunger to carve an alternative path, the squatters’ lifestyle immediately appealed to him. “I had no plan, no money and no job,” he remembers. “But I had a craving for life, for extreme experiences and I wanted to go beyond my comfort zone.”

After graduating from his art master’s in Poland, Pawel Dziemian arrived in London in August 2009 and was introduced to the squatting scene through a friend. With no plans after finishing university and a hunger to carve an alternative path, the squatters’ lifestyle immediately appealed to him. “I had no plan, no money and no job,” he remembers. “But I had a craving for life, for extreme experiences and I wanted to go beyond my comfort zone.”

Over the next two years, Pawel lived in a series of squats, in Walworth, New Cross and across South London. Picking up his camera, he shot an intimate portrait of life in London’s many squatted houses and commercial buildings – even dropping in to document squats north of the river, in Hackney and elsewhere, too.

Over the next two years, Pawel lived in a series of squats, in Walworth, New Cross and across South London. Picking up his camera, he shot an intimate portrait of life in London’s many squatted houses and commercial buildings – even dropping in to document squats north of the river, in Hackney and elsewhere, too.

In the wake of the 2007 financial crisis, it was a time when people were coming together to challenge the powers that be. “Financial crisis, credit crunch, Occupy movement, going green and student protests: I think back then we felt that we could shape socio-political reality,” Pawel reflects.

This hunger for change was widespread, but particularly resonated in London’s squat communities. “Squatting was particularly important then because it provided an alternative scene and space for young creatives of all kinds,” he says. “It also helps to tackle homelessness and the lack of adequate housing, in general. The legal protections provided to squatters support the less privileged, vulnerable urban dwellers, when the state usually sides with the landlords and big capital.”

Squatting in commercial properties is still legal, but the British government criminalised residential squatting in 2012. Combined with the meteoric rise of the property market and development, which has swallowed up much of the empty housing stock, the law change has reduced the proliferation of squats in the capital – but the community is still active and squatting remains a defiant protest against inadequate housing and inequality.

But even before the law change, the life of a London squatter was still chaotic and unpredictable – but also exciting, sociable and creatively stimulating, which is why Pawel picked up a camera to begin documenting life around him. “There were a number of reasons I began shooting,” he says, “but above all it was a search for beauty: beauty in leftovers of consumer reality, beauty in the grime and the cold.

“Looking back, I would also say that the camera was helping to deal with the unpredictable, tough conditions of squatting life. In those two years, the lens become a kind of barrier separating myself from the subject, from the sometimes harsh surroundings. There were many times I couldn’t shoot, when I wasn’t comfortable enough to separate myself from reality – like the two times I was arrested for squatting, for example.”

In hindsight, Pawel feels much of the optimism of those years he spent squatting in buildings around London is gone. “After the financial crisis, many people believed that we might be able to change the world,” he reflects. “Nowadays, London and the UK appear more and more capitalistic, like New York and America, where every man is for himself and everyone has to be entrepreneur. ‘Business as usual’ won again.”

In hindsight, Pawel feels much of the optimism of those years he spent squatting in buildings around London is gone. “After the financial crisis, many people believed that we might be able to change the world,” he reflects. “Nowadays, London and the UK appear more and more capitalistic, like New York and America, where every man is for himself and everyone has to be entrepreneur. ‘Business as usual’ won again.”

Find out more about Pawel Dziemian’s work.

Find out more about Pawel Dziemian’s work.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.

Latest on Huck

Meet the trans-led hairdressers providing London with gender-affirming trims

Open Out — Since being founded in 2011, the Hoxton salon has become a crucial space the city’s LGBTQ+ community. Hannah Bentley caught up with co-founder Greygory Vass to hear about its growth, breaking down barbering binaries, and the recent Supreme Court ruling.

Written by: Hannah Bentley

Gazan amputees secure Para-Cycling World Championships qualification

Gaza Sunbirds — Alaa al-Dali and Mohamed Asfour earned Palestine’s first-ever top-20 finish at the Para-Cycling World Cup in Belgium over the weekend.

Written by: Isaac Muk

New documentary revisits the radical history of UK free rave culture

Free Party: A Folk History — Directed by Aaron Trinder, it features first-hand stories from key crews including DiY, Spiral Tribe, Bedlam and Circus Warp, with public streaming available from May 30.

Written by: Isaac Muk

Rahim Fortune’s dreamlike vision of the Black American South

Reflections — In the Texas native’s debut solo show, he weaves familial history and documentary photography to challenge the region’s visual tropes.

Written by: Miss Rosen

Why Katy Perry’s space flight was one giant flop for mankind

Galactic girlbossing — In a widely-panned, 11-minute trip to the edge of the earth’s atmosphere, the ‘Women’s World’ singer joined an all-female space crew in an expensive vanity advert for Jeff Bezos’ Blue Origin. Newsletter columnist Emma Garland explains its apocalypse indicating signs.

Written by: Emma Garland

Katie Goh: “I want people to engage with the politics of oranges”

Foreign Fruit — In her new book, the Edinburgh-based writer traces her personal history through the citrus fruit’s global spread, from a village in China to Californian groves. Angela Hui caught up with her to find out more.

Written by: Katie Goh