Photos envisioning a world free from injustice

- Text by Miss Rosen

- Photography by Tyler Mitchell, Still from Idyllic Space, 2019 © the artist (main image)

Utopia is available to all who call upon their imagination to conjure the perfect world. And who better than the artist to visualise an escape from the infernal damnations of the earth and offer a visionary portrait of a future we might dare to dream into existence?

In ‘Utopia’, Aperture #241, artists, photographers, and writers come together to envision a world without prisons, sexism, racism, xenophobia, homophobia, environmental collapse – and all the other dangers pushing our very existence over the precipice.

Featuring the work of Nicole R. Fleetwood, The Family Acid, Lina Iris Viktor, Mickalene Thomas, Lorna Simpson, among others, Utopia offers a panoply of possible futures at our fingertips: a world without prisons, where people from all walks of life are free and unhindered by the spectre of oppression on every level of existence, starting with the relationship between artist and subject.

Tyler Mitchell, Untitled (Family Time in the Park), 2019 © the artist

Tyler Mitchell, Untitled (In the Blue Bush), 2018 © the artist

“Inherent to photography, especially when you think of it historically, is a strong hierarchy, where the photographer is the one with all the power, the one who is seeing. And the person being seen has almost no power,” Tyler Mitchell says of his work, which envisions Black liberation as the expression of peaceful repose, in an interview with Aperture.

“As a photographer, I ask myself, ‘What are the things I can do to lessen these inherent hierarchies in the photography-shoot structure of seeing and being seen?’”

Mitchell’s question underpins all the works collected here, which plumb the depths of our individual and collective imaginations to consider how a new world would look, and the role of photography in transcending the limitations of time and place.

The stories featured in Utopia offer new ways to consider the every day and the extraordinary as two sides of the same coin. Allen Frame’s 1981 photographs of the downtown New York scene just before the AIDS pandemic devastated a generation reminds us that utopia can be a matter of perspective about the here and now.

Biospherian candidates, 1990, from the film Spaceship Earth, 2020. Courtesy Matt Wolf

Biosphere 2, ca. 1991, from the film Spaceship Earth, 2020. Courtesy Matt Wolf

For American photographer Balarama Heller, utopia is “a personal and collective process, not an attainable external state”. In the 2019 series Sacred Place, currently on view in an online exhibition, Heller brings us to Vrndavana, a place of pilgrimage southeast of Delhi for the Hare Krishna movement, a faith in which he was raised during the 1980s.

Heller set out on the pilgrim road to encounter what mystery might be present, making photographs between three and six in the morning – a sacred time before sunrise where the boundary between the material and spiritual world is thin and porous. “The world has yet to assume its hardened shape made clear by the light of the sun and the energies of devotion are fuelled by the intimacy of the predawn darkness. Things take on an otherworldly glow and while the rest of the world sleeps, a divine presence is imbued in the most ordinary objects,” he explains.

Ultimately, utopia can be founded wherever we are, provided we are willing to do the work. As Heller observes, “The best we can do is be the change we want to see in the world, and that might just be enough to make the world a more equitable, sustainable place.”

Laurent Kronental, Denise, 81 years, Cité Spinoza, Ivry-sur-Seine, 2015 © the artist

Balarama Heller, Offer Nothing, 2019. Courtesy the artist

Allen Frame, Cady Noland and Butch Walker at the beach, from the series 1981, NYC, 1981. Courtesy the artist and Gitterman Gallery, New York

Amarise Carreras, el jíbare reza por amor (El jíbare prays for love), Queens, 2019. Courtesy the artist

Aperture’s ‘Utopia’ issue is available on their official website.

Follow Miss Rosen on Twitter.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.

Latest on Huck

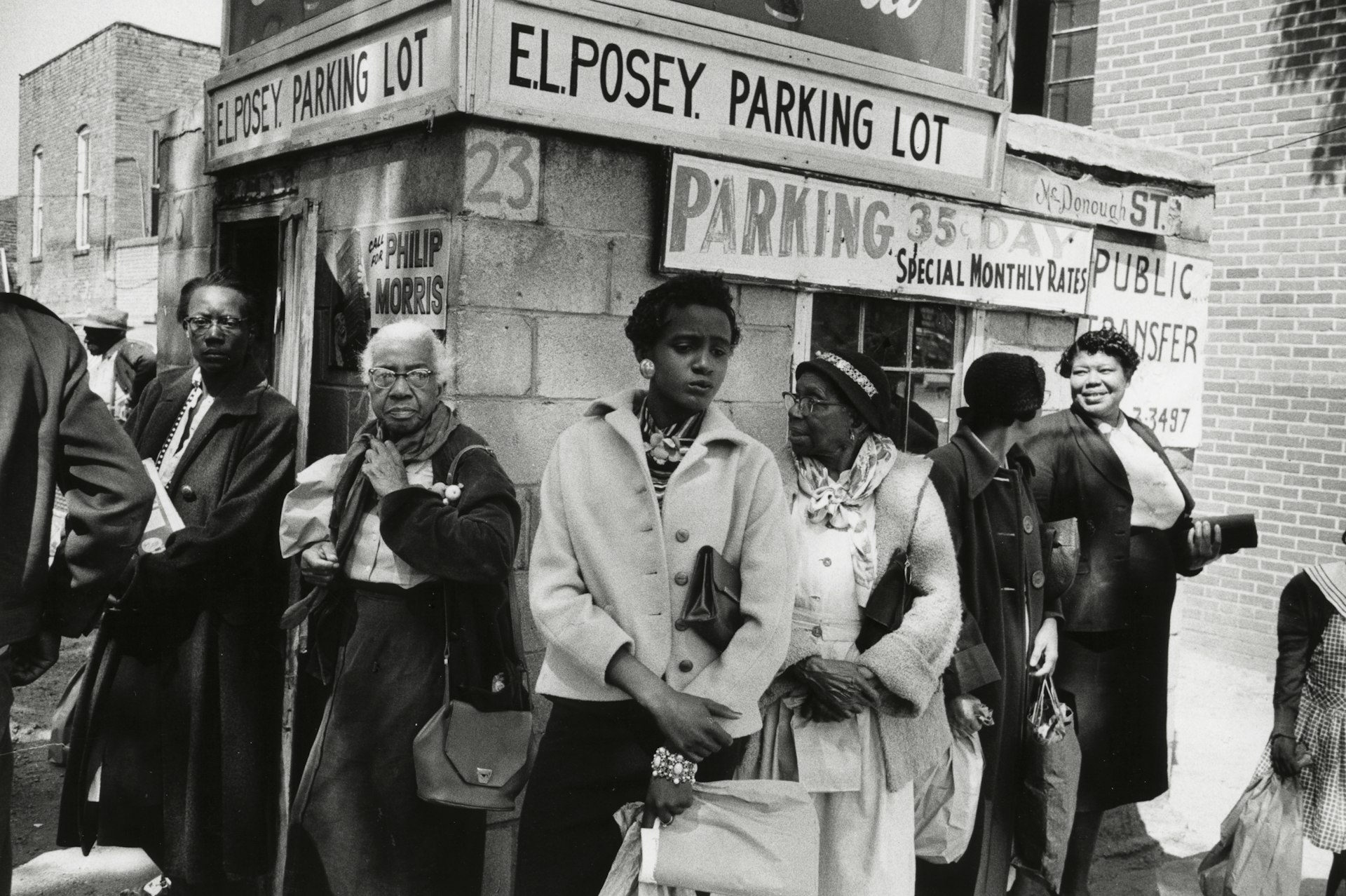

How Labour Activism changed the landscape of post-war USA

American Job — A new exhibition revisits over 70 years of working class solidarity and struggle, its radical legacy, and the central role of photography throughout.

Written by: Miss Rosen

Analogue Appreciation: Emma-Jean Thackray

Weirdo — In an ever more digital, online world, we ask our favourite artists about their most cherished pieces of physical culture. Today, multi-instrumentalist and Brownswood affiliate Emma-Jean Thackray.

Written by: Emma-Jean Thackray

Meet the shop cats of Hong Kong’s Sheung Wan district

Feline good — Traditionally adopted to keep away rats from expensive produce, the feline guardians have become part of the central neighbourhood’s fabric. Erica’s online series captures the local celebrities.

Written by: Isaac Muk

How trans rights activism and sex workers’ solidarity emerged in the ’70s and ’80s

Shoulder to Shoulder — In this extract from writer Jake Hall’s new book, which deep dives into the history of queer activism and coalition, they explore how anti-TERF and anti-SWERF campaigning developed from the same cloth.

Written by: Jake Hall

A behind the scenes look at the atomic wedgie community

Stretched out — Benjamin Fredrickson’s new project and photobook ‘Wedgies’ queers a time-old bullying act by exploring its erotic, extreme potential.

Written by: Isaac Muk

“Welcome to the Useless Class”: Ewan Morrison in conversation with Irvine Welsh

For Emma — Ahead of the Scottish author’s new novel, he sat down with Irvine Welsh for an in-depth discussion of its dystopic themes, and the upcoming AI “tsunami”.

Written by: Irvine Welsh