Portraits of revellers at the birth of Northern rave culture

- Text by Ella Glover

- Photography by Steve Lazarides

When Steve Lazaridez began taking portraits of people dancing in the UK’s first illegal raves, he couldn’t predict how people would react. “He went from this kind of vitriolic, spitting in your face, ‘fuck off or I’ll kill you,’” recalls the British-Greek Cypriot publisher, photographer, collector and curator, of the time he unknowingly asked a man who had just come out of prison whether he could take his picture. “Then, 10 minutes later he came back and said, ‘right, my pill’s kicked in, you can come and take my picture if you want.’”

It was around 1992 and Lazarides was a 22-year-old photography student at Newcastle Polytechnic. With a budget that stretched to just one roll of film a night, he decided he wanted to capture the emergence of the enigmatic UK rave scene. Now, 30 years on, these photos are collected in a new book titled Rave Captured.

Lazarides says that rave culture was never exactly his scene, but he’d wanted to show a different side to how it was being portrayed by the fear-mongering press. For Lazarides, the scene was more than what he calls in the book “a simmering pot of depravity,” but a place where people went to express their freedom. “It was the mass lawlessness that appealed to me,” he tells Huck. “I’ve never been one for rules and regulations at the best of times and, to be there, seeing everybody breaking it on a mass level, was quite something.”

As someone with bipolar and ADHD, both undiagnosed until his mid-40s, Lazradies has always been attracted to subcultures. First, it was graffiti, then skateboarding. Then, he tells Huck, “While I was at college, the Bristol scene sort of unfolded in front of my very eyes – I still kick myself to this day for having never taken a single picture of it.”

Still, he felt like an outsider to the rave scene. “It was a privilege to be granted access because, as with most subcultures, the only pictures that really count are the ones that tend to be taken by people that are already immersed in something.”

Despite a certain wariness of cameras from within the subculture, mostly due to the demonising press reports and a lack of non-press photographers around at the time, Lazarides began to gain people’s trust: “I’d go to the rave and I suddenly started seeing some of the same characters there, so there was a little bit of camaraderie.”

It’s this trust, he believes, that allowed him to take such authentic portraits – and that’s why he’d always asks permission before taking a photograph. “When you take a good portrait, it does have a bit of someone’s soul in it,” he says. “You get some feeling for who the person is, and that’s a big ask. That’s why I maintain, if you haven’t got the bollocks to ask someone if you can take their photograph, you don’t have the right to take it.”

It wasn’t easy – for every ‘yes’, he recalls, he would get about five “fuck off or I’ll kill you’s”. But, he says, you need to spend time with the people you’re photographing. “You can still get those off-key portraits,” he says, “You’ve just got to put the time and effort in.”

The rave scene erupted out of the ruins of Thatcher’s Britain which, especially in the North East, had decimated industry. “Suddenly, you’re watching a society trying to repair the wounds of a fucking lunatic,” Lazarides says. “And people just wanted to step out and fucking party.”

He continues: “You can only feel glum for so long, before you have to slap on your war paint and your armour and go and live life.

“It was us against the state; It was a big fuck you to the press and society, without it really being about that. People weren’t doing it as a mass protest, they were doing it because they wanted to have a good time again…But I’ll tell you what, it didn’t feel like we were losing.”

Rave Captured is available to purchase here.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.

Latest on Huck

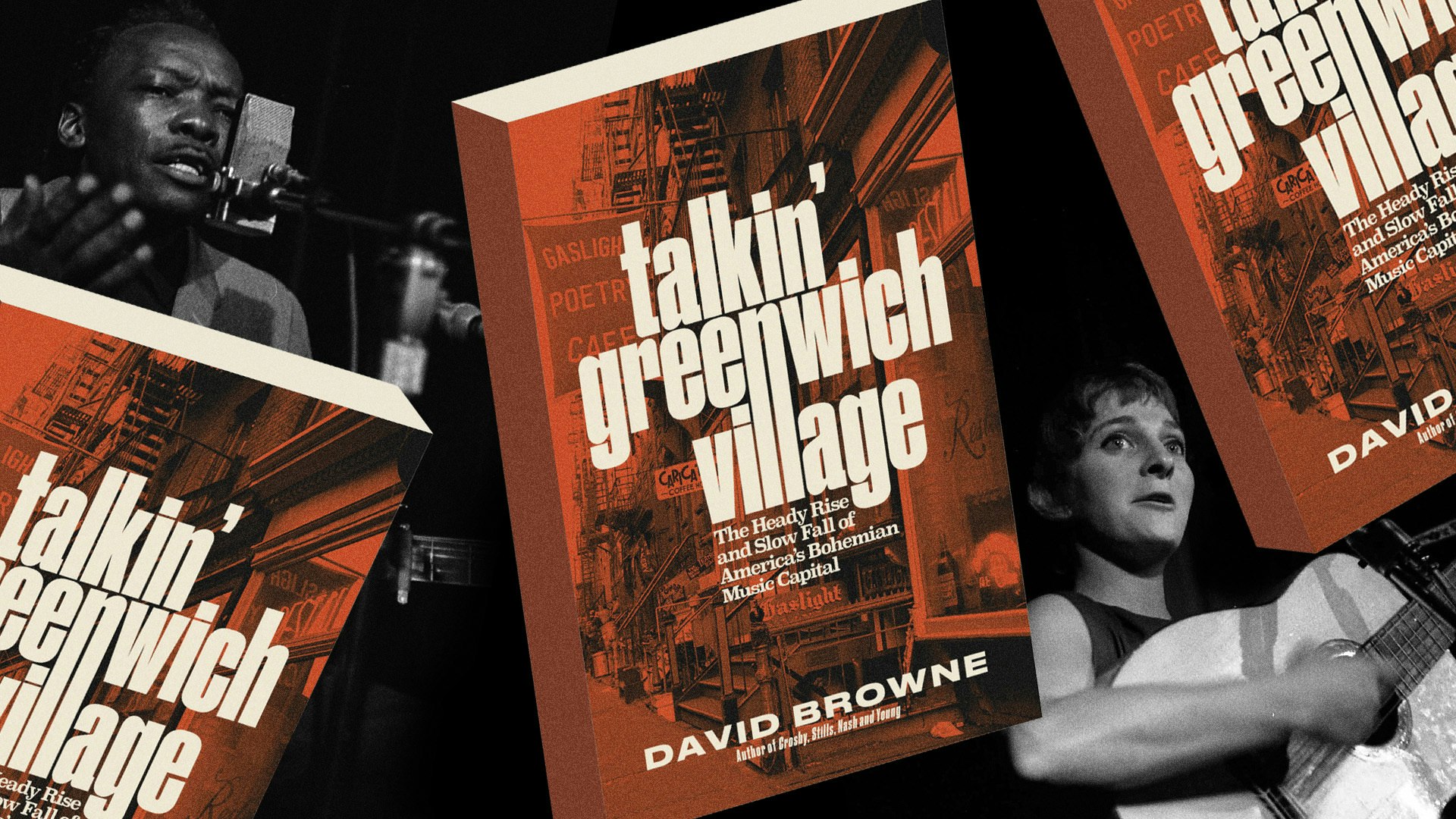

In the ’60s and ’70s, Greenwich Village was the musical heart of New York

Talkin’ Greenwich Village — Author David Browne’s new book takes readers into the neighbourhood’s creative heyday, where a generation of artists and poets including Bob Dylan, Billie Holliday and Dave Van Ronk cut their teeth.

Written by: Cyna Mirzai

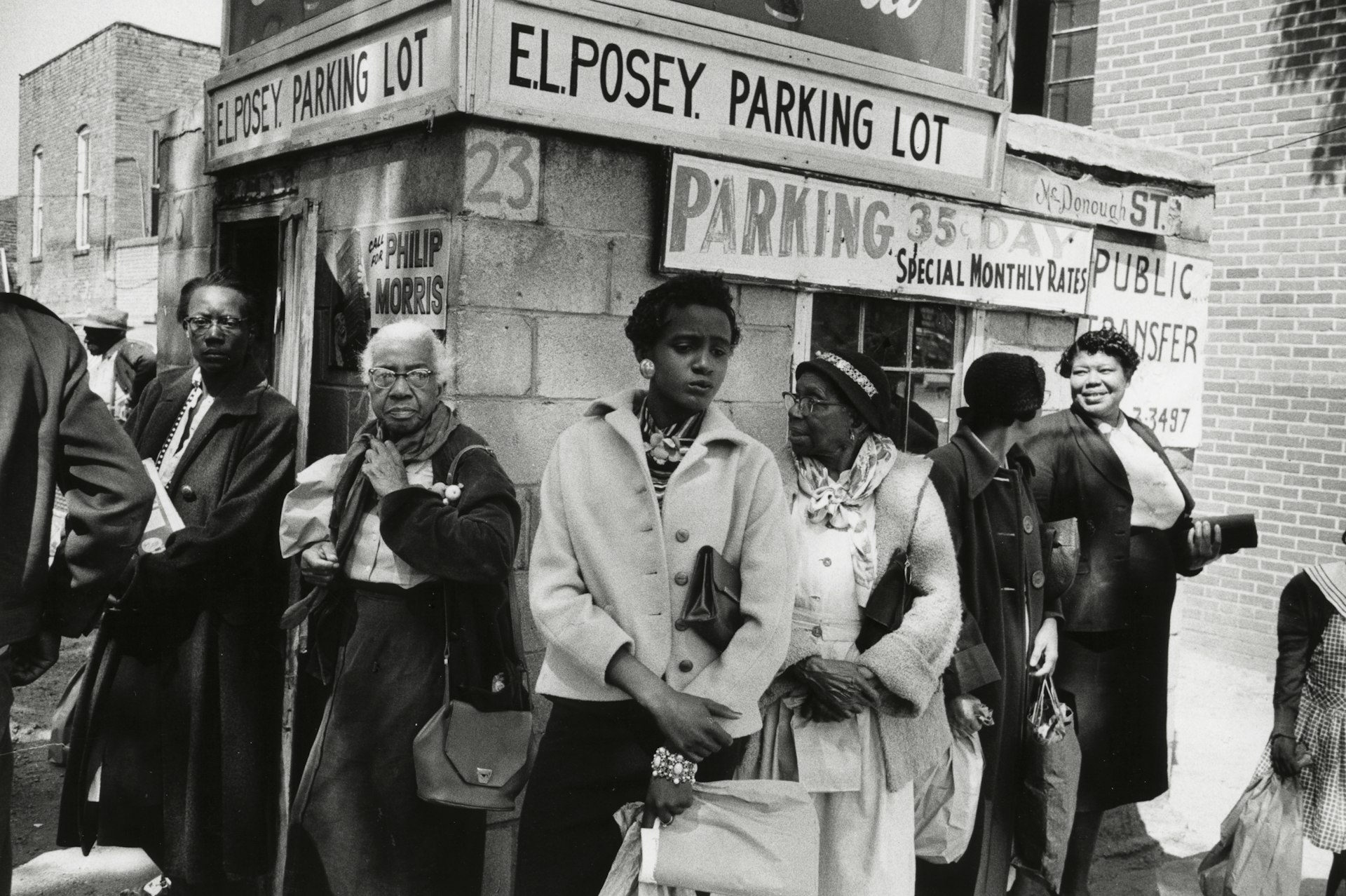

How Labour Activism changed the landscape of post-war USA

American Job — A new exhibition revisits over 70 years of working class solidarity and struggle, its radical legacy, and the central role of photography throughout.

Written by: Miss Rosen

Analogue Appreciation: Emma-Jean Thackray

Weirdo — In an ever more digital, online world, we ask our favourite artists about their most cherished pieces of physical culture. Today, multi-instrumentalist and Brownswood affiliate Emma-Jean Thackray.

Written by: Emma-Jean Thackray

Meet the shop cats of Hong Kong’s Sheung Wan district

Feline good — Traditionally adopted to keep away rats from expensive produce, the feline guardians have become part of the central neighbourhood’s fabric. Erica’s online series captures the local celebrities.

Written by: Isaac Muk

How trans rights activism and sex workers’ solidarity emerged in the ’70s and ’80s

Shoulder to Shoulder — In this extract from writer Jake Hall’s new book, which deep dives into the history of queer activism and coalition, they explore how anti-TERF and anti-SWERF campaigning developed from the same cloth.

Written by: Jake Hall

A behind the scenes look at the atomic wedgie community

Stretched out — Benjamin Fredrickson’s new project and photobook ‘Wedgies’ queers a time-old bullying act by exploring its erotic, extreme potential.

Written by: Isaac Muk