A photographic catalogue of subcultures that refuse to die

- Text by Cian Traynor

- Photography by Owen Harvey

Late one balmy August night in 2016, Owen Harvey stood outside Manhattan’s Bryant Park, nervously awaiting an encounter that would determine the next three months.

Back in England, the photographer had spent the previous five years documenting two stylish subcultures – mods and skinheads – that exist outside of time.

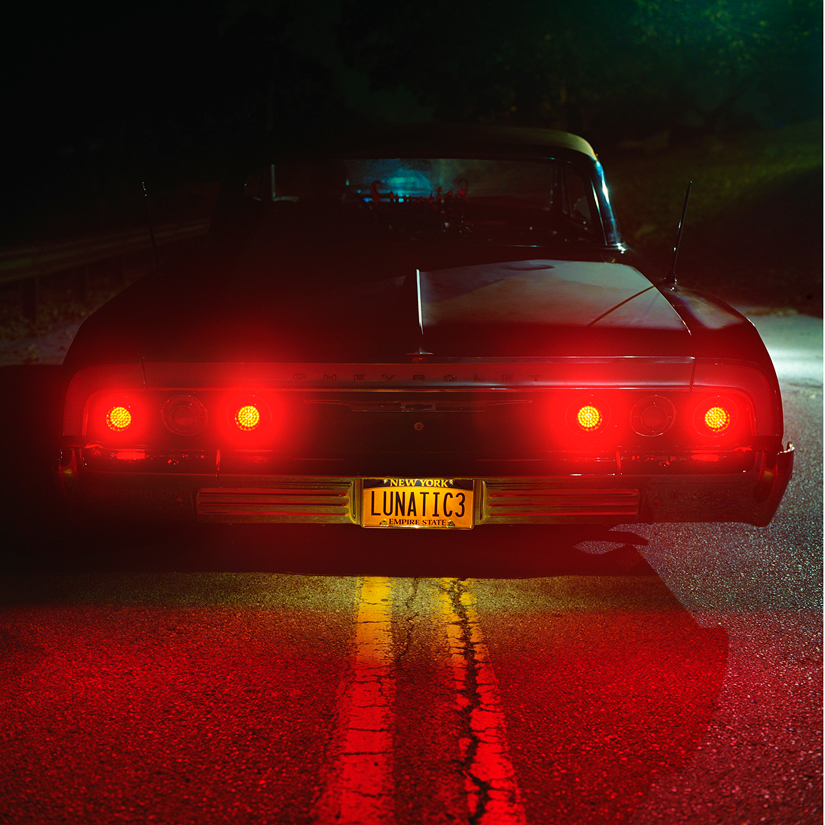

It had taken countless hours of developing contacts, earning trust and spending all his money on film. Now he was trying to pull off something similar in America via the Lunatic Lowriders: a heavily tattooed community built around cruising vintage cars.

Dyablo and Andreas, The Bronx, NYC.

But after saving up to fly over – the 26-year-old’s first major trip abroad – they hadn’t returned his calls until two weeks in, when he was directed towards midtown Manhattan at the last minute. An hour of waiting went by. It started to feel like it wasn’t meant to be, that maybe he had finally overreached.

Then he heard a rumble in the distance. A convoy of tricked-out convertibles snaked its way toward him, a blaring PA system spread across the backseat of one car.

“We just cruised around the whole of Manhattan until three in the morning, pumping all the music I listened to as a teenager,” he says, beaming. “You can’t imagine how much a skinny white kid with an English accent stuck out; it felt like I’d stepped into a movie.”

Today Owen is seated in a nook at the back of Huck’s gallery in Shoreditch, a hardback portfolio open in front of him, plotting out his route to that point. It started at the University of South Wales in Newport, where he studied documentary photography.

When it came time to focus on a graduation project, an old school friend pointed Owen towards the mod scene: a relatively close-knit community that occupied a world of its own.

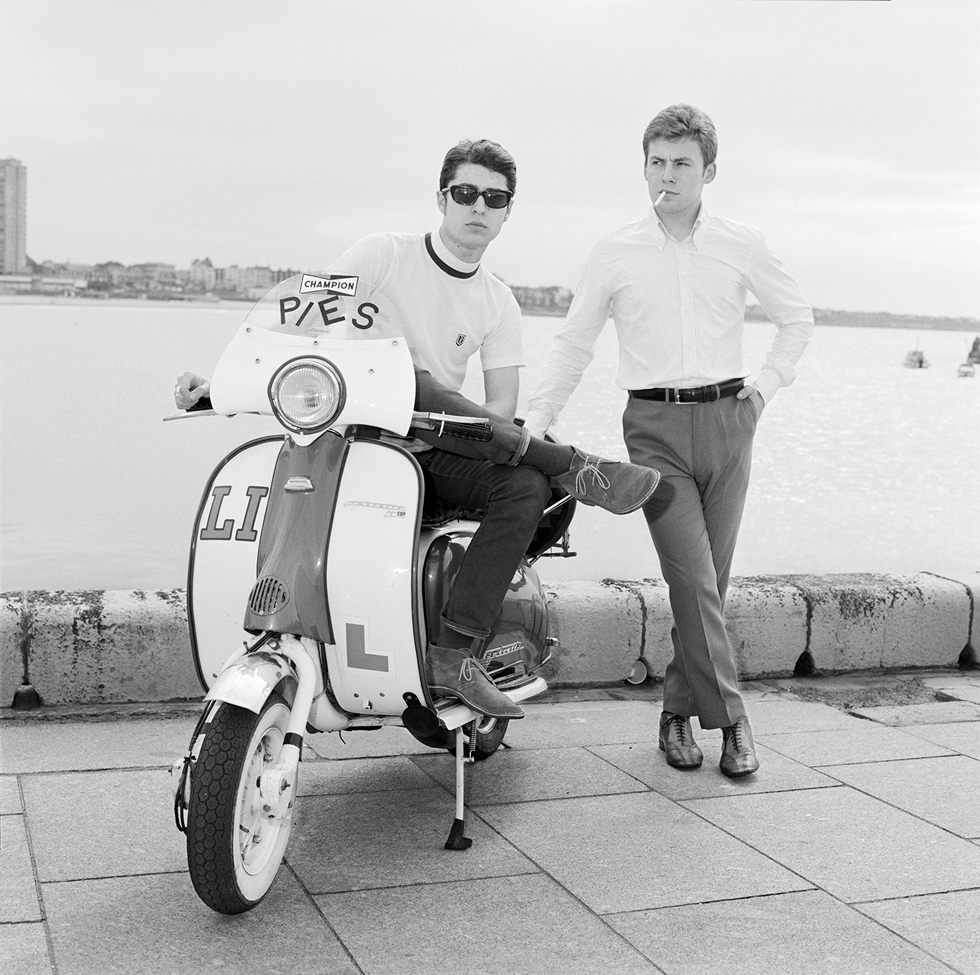

‘Mod’ is an abbreviation for modernism, an umbrella term coined in the late 1950s to cover a set of intertwined subcultures – fashion, music, scooters, dancing – that carried an air of exclusivity. But it was also just a way for people to look like a million quid on the weekend, even if their bank balance didn’t necessarily reflect that.

Rachel & Josh.

So when Owen showed up in jeans and a t-shirt, with everyone else wearing tailored suits, he felt like an outsider immediately. “Quite naively, because it was my first project, I thought that everyone would be cool with me just rocking up and putting cameras in their face,” he says, laughing.

“But from going to pretty much every club night over the course of a year, they could see that I was developing a project I was committed to. I think it helped that I was honest, that I was really into the music and didn’t care if I stuck out like a sore thumb.”

Something magic happened that first night. Amid some blank frames and blurred exposures taken out of sheer excitement, a handful of images nailed the subculture’s timeless appeal – inspiring Owen to spend years documenting Mods all across England.

Along the way, certain values became clear: attention to detail, respect for heritage and a rejection of throw-away fashion. A lot of Mods work as designers or stylists, Owen says, so an element of competition can surface when they get together.

Max and Alex.

The level of investment in making sure everything looks just right – from a perfectly placed pocket-square to the sharpest cufflinks – is enough to make more obvious choices look laughable by comparison.

“They know exactly how they want to be portrayed,” he says. “For most photographers, taking a portrait is an impossible attempt to get underneath the skin of someone. This is the complete opposite: they’re giving you this thing in their head, the way they want to construct themselves, which in turn is letting you know so much more about them.”

Lara, Brighton.

Over time, Owen noticed some nuance beneath the surface. Once, in Brighton, he met a teenage couple styled from bygone eras: Lara was a mod, Jamie a skinhead. Together, they made for a bold sight. Up close, they seemed quiet and reserved, clinging to each other as if out of necessity.

“Although they’d both decided to be involved in different subcultures, it made me realise that perhaps the specific one they aligned themselves with wasn’t that relevant,” he says. “It was really more about holding onto something and being part of a community in which they could find friendships.”

That sense of belonging rose to the fore of Owen’s work once he began documenting skinhead culture. It was on another trip to Brighton that he struck up a friendship with Billy and Freya at an event called The Great Skinhead Reunion.

The photographer has a natural ability to spark a rapport, which is something he continually relies on to develop access. So when the couple welcomed him into their circle, dismantling any preconceptions he might have had about skinheads, his day-trip turned into three days of drinking beer in the sun.

Freya & Billy.

Billy – an outgoing guy in his thirties devoted to the semi-pro football club Whitehawk – had the air of a natural leader. He may look intimidating in the photos, Owen says, but he couldn’t have been nicer.

So one invitation led to another until the photographer found himself sharing a ramshackle room in a Blackpool B&B, sleeping on a dressing gown as Billy and friends got drunk out of their minds.

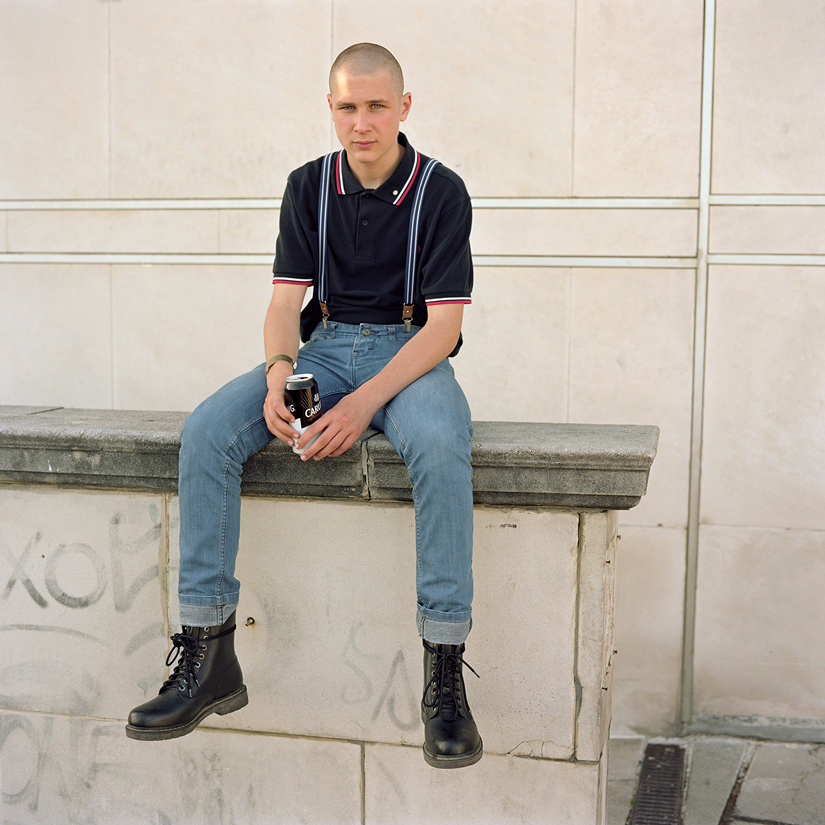

Jamie.

“Once you spend three nights together in a place like that, there’s a bit more understanding and trust – it felt like a door opening,” he says. “They’re very conscious of how they’re perceived because the whole skinhead thing has only had negative attention.”

Its complex history, he explains, began when Mod style integrated with music imported from Jamaica in the 1960s. There was a sense of working-class pride and social alienation shared by black and white youth across England, with the skinhead image coming to represent – in part – a rejection of conservative values.

Billy, Blackpool.

But by the 1980s, a second-wave of skinheads split into factions: the apolitical, the far-left and the far-right. Media coverage of the latter grew so sustained that skinheads became associated with neo-Nazis and football hooligans, forcing many to abandon it altogether. The ones Owen spent time with want to reclaim that image from fascists and restore the subculture’s roots.

As with Mods, he detected a clear emphasis on heritage, an impulse to ‘peacock’ as well as a gulf between their identity and how they’re perceived by the wider world. But the stakes are much higher on a personal level, as many have been verbally attacked in the street by those who misunderstand what they represent.

Mollie.

“For a lot of them, it’s a big ‘fuck you’ to the media,” says Owen. “It’s like, ‘You’ve only reported one part of it but this other part still exists and we’re not going to let go of that just because it’s been sabotaged.’

“Obviously it’s a bold choice because it has so many negative connotations. One of the lads abandoned it for about six months. He was like, ‘I can’t be bothered with the bullshit it brings anymore.’ Eventually he thought, ‘You know what? Fuck those people. Why should I change because of others’ ignorance?’”

Owen puts his ability to mix well with others down to a broad family background. He grew up in Watford, on the outskirts of London, with a private school teacher for a mother and a fireman for a father. That both sides of the family were so incredibly different taught him to adapt in any situation. But when it came time to find another new project, he wanted to see how he’d cope much further from home.

As a teenager, Owen listened to a lot of hip hop. He remembers hanging out in his older brother’s bedroom, sneaking sips of cider and watching the Up in Smoke Tour on DVD – a lowrider rolling out on stage just as Dr. Dre launched into the encore. “Those sounds felt like they couldn’t have been further removed from my existence.”

A couple of years ago, while working in a photo lab, Owen started remembering how invested he’d once been in that world, how exotic it all seemed. So he saved up, did some research and that’s how he came across the Lunatic Lowriders – a well-known ‘cruising club’ founded by Willy, a union construction worker, and Julio, who owns a produce distribution centre in the Bronx.

In New York, Owen gradually networked his way from one portrait opportunity to another – returning for a total of four trips – learning as much as he could about the subculture in the process.

It started in the 1950s, he explains, when young Mexican-Americans began customising affordable family cars to look more desirable. They’d decorate them with political statements and emblems of Latino culture, then use sandbags to make the car ride “slow and low” as if on parade.

They even formed clubs, complete with membership fees and in-house rules, intent on outshining rivals. So as it turned out, lowrider culture has a lot in common with Owen’s other projects: style, heritage, working-class pride and musical iconography. And at the end of that first trip, when various cruising clubs got together at a barbeque, all those elements converged in one big party.

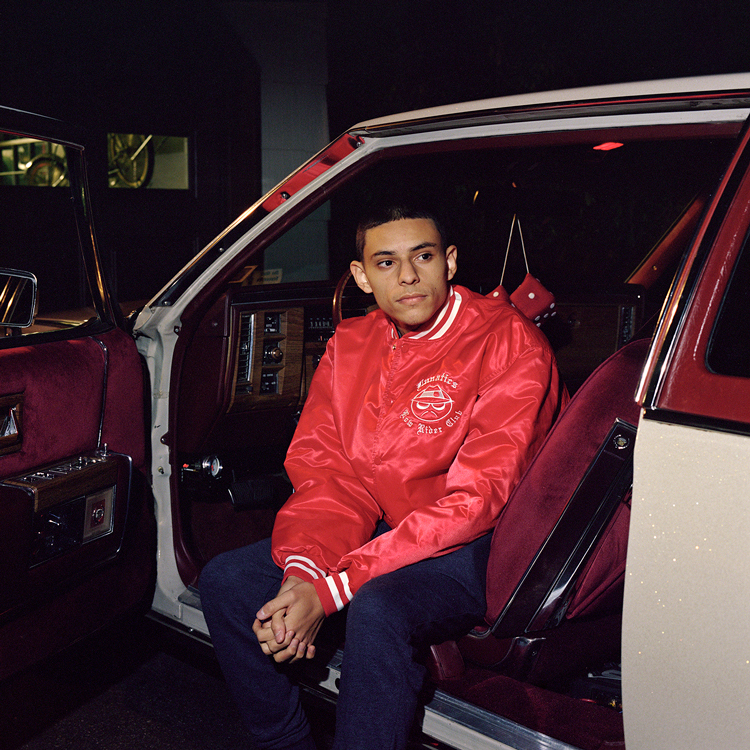

Sosa, Harlem, NYC.

“I was nervous going up to these intimidating-looking guys five times the size of me, asking if they could take their top off,” he says. “They’re all bravado in front of each other and don’t want to seem like they want their picture taken, but they really do,” he says.

“It means so much to them, so it’s no surprise they go cruising down by Times Square – it’s the biggest tourist spot and people are guaranteed to pay attention.”

That desire to be seen runs right through Owen’s portfolio. As he flicks through the pages, the edge of a tattoo jutting out from his shirt sleeve, it seems like a good opportunity to ask what attracts him to these characters.

Until recently, he would have simply said that it’s the level of investment. That single-minded focus is something that’s been with him for as long as he can remember.

Recently, though, a photographer pointed out another theme: that these subcultures are loaded with machismo. It rang true in a way that made Owen rethink the work.

Sanchez, Tarry Town, NYC.

“Whether they like to admit it or not, I think all men are interested in macho characters. Maybe you see your uncle or your dad in that person. Maybe it’s the element of danger, of things that you don’t understand but, deep down, are excited by. Maybe it’s just that ability to showboat and project how you want to be perceived.”

Owen recognises some of that within himself. Before the lowriders project, he struggled to admit he was still learning. In fact when he showed up in New York, determined to make it work, he kept repeating a familiar refrain: “I can’t fail. I can’t fail. It’s gotta be great.” Looked at in a different light, he wonders if maybe these projects – and his own approach to them – might be digging at something bigger.

Craig-O, Lunatics Lowrider Club, NYC .

“There’s a tendency for guys to set outrageous fucking targets for themselves and then, when they can’t reach them, suffer quietly in their own mind,” he says.

“I think all of these ideas are involved in my practice in some way and I don’t quite understand where at the moment… But it’s made me realise that the more I delve into these other worlds, the more perspective I have on my own life.”

This article appears in Huck 63 – The Fantasy Issue. Buy it in the Huck Shop or subscribe to make sure you never miss another issue.

Check out Owen Harvey’s portfolio.

You might like

A new documentary traces the rise, fall and cratering of VICE

VICE is broke — Streaming on MUBI, it’s presented by chef and filmmaker Eddie Huang, who previously hosted travel and food show Huang’s World for the millennial media giant.

Written by: Ella Glossop

Warm, tender photos of London’s amateur boxing scene

Where The Fire Went — Sana Badri’s new photobook captures the wider support networks and community spirit around the grassroots sport, as well as the significance of its competitions to the athletes who take part.

Written by: Isaac Muk

As Kneecap and Bob Vylan face outcry, who really deserves to see justice?

Street Justice — Standing in for regular newsletter columnist Emma Garland, Huck’s Hard Feelings host Rob Kazandjian reflects on splatters of strange catharsis in sport and culture, while urging that the bigger picture remains at the forefront of people’s minds.

Written by: Robert Kazandjian

“Moment of escape”: Maen Hammad’s defiant West Bank skate photos

Landing — Choosing to return to Palestine after growing up in the USA, the photographer found himself drawn to Ramallah’s burgeoning skate scene. His debut monograph explores the city’s rebellious youth, who pull tricks in the face of occupation.

Written by: Miss Rosen

Inside the weird world of audio porn

Porn without pictures — Storyline-driven and ethical, imageless erotica exploded during the pandemic. Jess Thomson speaks to the creators behind the microphones.

Written by: Jess Thomson

We are all Mia Khalifa

How humour, therapy and community help Huck's latest cover star control her narrative.

Written by: Alya Mooro