The Swinging Man: Huck meets Henry Rollins

- Text by Steven T. Hanley

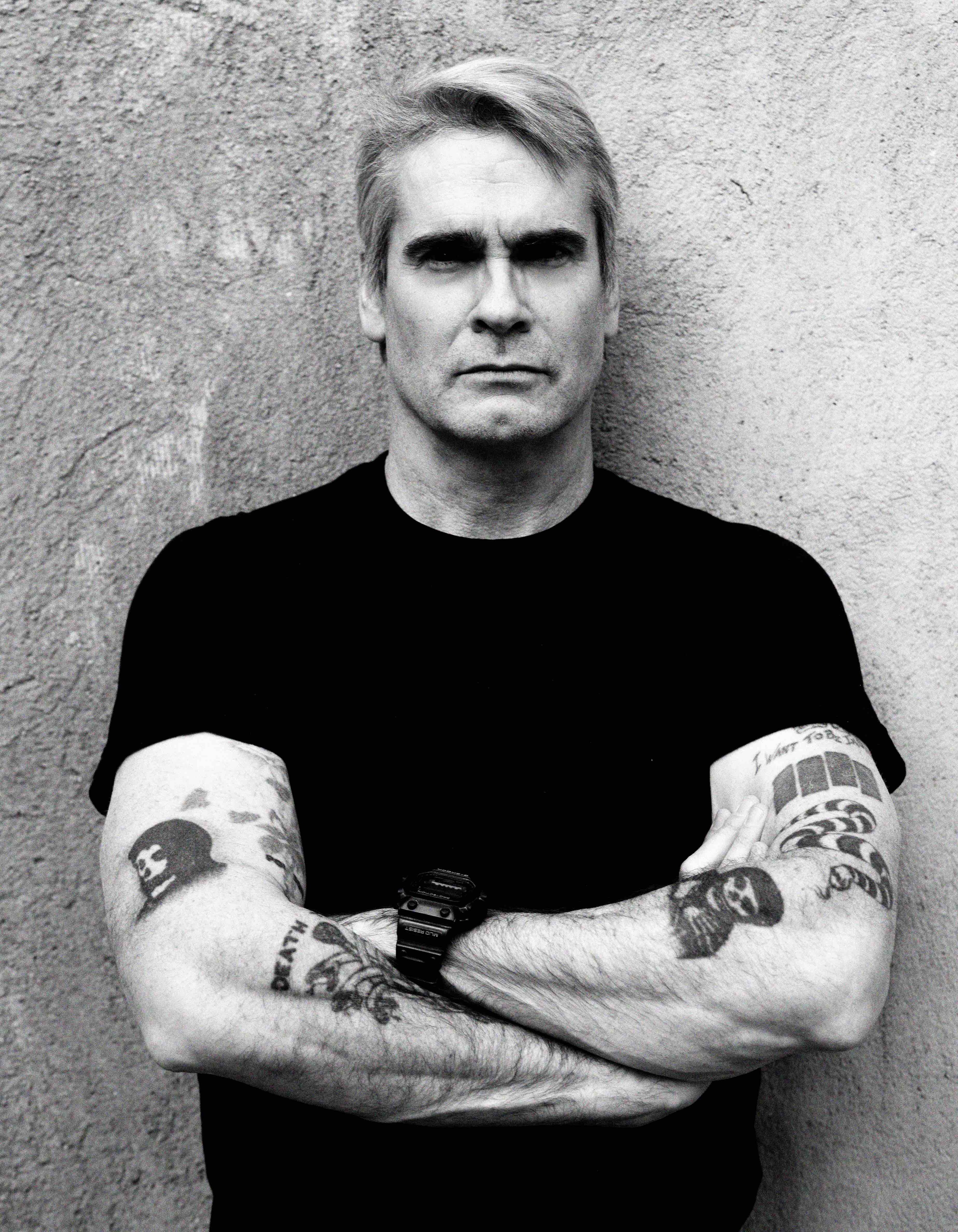

- Photography by Heidi May

I’m a work guy. I’ve always been the work guy, I’ve never cared much about the fame aspect or popularity. I’m like the mechanic under your car, I only care about getting the thing on the road.”

Henry Rollins cannot sit still.

In 1981, aged just twenty, Rollins left everything he knew in Washington DC – where he and closest ally Ian MacKaye (mastermind behind Minor Threat and Dischord Records) were the gravitational centre of a flourishing music community – and moved to California to front hardcore punk band Black Flag.

The group went on to become underground legends, famous as much for their intense work ethic as their music. Rollins served for five years as Flag’s unbreakable muscle-bound vocalist during a rebellious period marked by anarchic shows, chaotic tours, corrupt punk-hating cops and mind-numbing all-night tour drives.

Then in the mid-’80s, after Black Flag had split, partly due to that rigorous schedule and partly due to guitarist and founder Greg Ginn’s maddening mission to switch up the Black Flag sound at every opportunity, Rollins branched out to form the alt-rock Rollins Band. With his new line-up Rollins went on to make seven studio albums and then, with the same spontaneity in which he started his musical career, he made the radical decision to leave it all behind.

While some would happily bask in the cult status of being cited as one of the greatest frontmen in rock ’n’ roll – Rollins does not have time for that. He continues to work with the same level of power and drive that he’s become famous for on stage. He continually refocuses his energy: embarking on a diverse career as actor, author, DJ, TV and radio show host, publisher, spoken-word artist, photographer, and documentary and travel journalist – often reporting back from poverty-stricken and warn-torn countries.

Huck caught up with Rollins between a trip to the Antarctic and a global spoken-word tour, to talk defiance, reinvention and his workaholic fire.

When did you make a definitive decision to give up music and focus on travelling, writing and acting?

In 2006 my old bandmates, who I love dearly, got together and went to band practice. They contacted me from New York and said they were there, playing the old set from 1997, and that we should do some shows. I got curious and I went out there and all of a sudden I’m in a room with these guys for the first time in nine years. These are great people – they start playing the songs and they sound really good so I start singing and you get high for a moment and go, ‘Wow!’

So we did a tour for five weeks and we played very well, but by the third show I realised I shouldn’t be there. Every night I thought, ‘Okay, I’m going to do this thing for an hour, I’m going to hit it really hard and dig it but this is not real.’ It’s like porn, it’s completely gratuitous. You [the audience] all like these songs – we are going to play them for you and we are going to get paid. I finished the last show – which was conveniently in Los Angeles, where I live – put on a different pair of sweatpants, and without even saying goodbye to the band I left the dressing room, snuck out to the parking lot and drove home. I’ve only seen one of those guys since. I don’t hate them. Quite the opposite… I feel I sort of sold out by doing that tour because it’s exactly what I don’t want to do – relive the past.

There’s a great Miles Davis quote about his constant reinvention where he said, ‘I don’t want to be the yesterday guy.’ Yeah! And he didn’t give a damn what you thought. Miles is a guy, believe it or not, who I have taken a lot of cues from. Not musically, because he’s Miles Davis and I’m nobody, but I spent a lot of years listening to his music. When you hear him take one of the most amazing line-ups in jazz – Herbie Hancock and Wayne Shorter, all these people – and go, ‘See ya!’ people are like, ‘What?’ And Miles says ‘Yeah, I’m going into something else.’ The next year he’s on stage playing his horn through a wah pedal with a bunch of hairy guys doing scary funk music from another place. A lot of his fans went, ‘Okay, I’m done,’ and he went, ‘Okay, I’m moving on.’ [I admire] that kind of fierce adherence to the music and to what the music was telling him – the same with Coltrane.

Jazz players from the ’60s were really pushing boundaries… I think a lot of the jazz guys make rock ’n’ roll look really conformist. Jazz is really the punk rock [of that era]. That speaks to me very much. I don’t want to do anything fake and I’m not all that interested in going and doing old material. I already know where all the furniture is in that room and I’d have gentle debates with established rock stars about this. I won’t name names but I’ve said, ‘So why do you go up there and do the same songs every year?’ And they say, ‘It’s what people want to hear.’ And I’d say, ‘Okay, is that your job? To do what people want you to do?’ In Black Flag we would throw out all the old music, write all new music, and tour, and audiences were pissed! Screaming, ‘We wanna hear ‘Six Pack’!” Greg [Ginn] would say, ‘We’re moving on,’ and as tough as that was sometimes, with anger from the audience, I really thought that was the honest way to go about it. It’s basically like going through life without dyeing your hair and tightening up your face; I don’t wanna try and be twenty-five again. And for me doing old music would be doing that. I think it would be really depressing.

Addicted to Movement

Rollins was born Henry Lawrence Garfield in Washington DC. His parents divorced when he was three and he was raised by his mom who worked for a health education and welfare programme that sprung up under President Johnson. According to Rollins, “She was the government person that basically tried to make the public educational systems in America run better.”

Before he found music, a young Rollins buried his head in National Geographic magazines as a way, perhaps, to escape the prescriptive norms of conservative East Coast society. After dissolving the original Rollins Band line-up in 1997, he made his dreams manifest by travelling to Kenya, Madagascar and South Africa. The trip itched a restless impulse. “I came home and said that’s it,” says Rollins. “I am going to travel non-tour-wise to different countries. Now I’ve been to Africa thirteen or fourteen times, South East Asia, Central Asia, the Middle East and I just got back from Antarctica two days ago. I make a point of getting out and getting into it whenever the schedule allows.”

Were you engaged in politics or was it thrust upon you from your time in Black Flag and things you saw and experienced under the name of ‘punk violence’? My household was very political. My mother and father are politically very different, my mother is very left of centre and my father very right of centre. My father and mother divorced. I saw my father on the weekends and so I was raised by my mother and her Bob Dylan records and rejected by my father. I kind of came out on the ‘kumbaya’ side of things.

Black Flag would be extraordinarily political because we had so much police pressure and local political operatives would come to our shows and do press conferences about how we were evil and all of that, so it made me quite cynical about my government, who seem to hate me and not want me to exist. And so I pushed back; as hard as they laid it on me, I tried to lay it back on them. The cops would hassle us and we would go to the press and hassle them back as best we could. Of course when you’re feuding with the government, the government is going to win. So I’ve been politically aware on different levels since I was a very young person.

You’ve entertained the troops in the 2003 Iraq War. You’ve travelled with the USO (a non-profit organisation that provides services and live entertainment to United States troops and their families) eight times, including visits to bases in Kuwait, Iraq and Afghanistan twice. What compelled you to go to war zones? To see what I could learn. I’m not really concerned about when I die. Put it this way, I’d leave for Kabul today if I didn’t have to leave for New York tomorrow. If I could survive six weeks in Kabul without getting my head cut off or kidnapped I’d definitely go back. Even if there’s a risk of that I might go back anyway. I’m more interested in seeing and learning than having a long life so when someone says, ‘Hey, you’re going into a high-threat condition environment, are you sure you want to do that?’ I’m like , ‘YEAH!’ I took those opportunities, I was fascinated to go and I’m not a fan of war but I also know soldiers don’t dictate foreign policy so if you don’t like the Iraq War the army is really not the person to have the argument with. My beef was with Dick Cheney, George W. Bush, Paul Wolfowitz, William Kristol so when the USO said, ‘Hey, do you want to meet soldiers?’ I said, ‘Absolutely.’

I was thinking about the links in the way you travel now and the way Black Flag travelled on gruelling tours for little-to-no money, walking into sketchy situations. The violence of the hardcore era is in some ways similar to your travels today. I was raised a very middle-class conservative Caucasian boy in Washington DC. Never missed a meal, I never had a put-out moment. I lived in a tough town, I saw some things go down for sure, but then I joined Black Flag and all of a sudden I’m twenty and within two years I’d seen stabbings, drug deals, cops trying to plant drugs on me. I’d seen a different version of America. And it grew me up fast. You become quite adult and even jaded. I saw quite a bit in a short amount of time and it got more intense as it went by.

By 1986 it felt like I had been living for fifty years and it makes me very effective in [certain] environments. Like, I met a guy with his legs blown off and half his face gone and I could go and talk to him. I feel bad for the guy but I can be cheerful in front of him because I’m not horrified by what I’ve seen… The Black Flag years definitely informed me in what bad hands the world can throw at you, which makes almost everything else I do a walk in the park. Nothing I ever did with music or living was ever as hard as those five years in Black Flag.

In 2011 Henry Rollins released Occupants, a photobook chronicling his travels around the world.

How was the Rollins Band experience in comparison? The Rollins Band got very popular. Our living standards kind of shot up within eighteen months of being in that band – we were all paying our rent and got better financially and weren’t hand-to-mouthing it as much. I live fathoms below my means, I’m just not interested in living a different way. I make my own food, I go to the grocery store, I drive a Mazda, I wear clothes from the army surplus store that are easily replaceable. I’m a work guy… I’m not in it for the applause or the pay cheque I want to do something really well and really, really intensely. I’ve figured out that, in my life, I go for any opportunity where I can be full on.

Out of Fury

The success of the Rollins Band afforded Rollins new experiences and opportunities and he embraced them with the same conviction that had brought him to music. He found a skill and satisfaction in acting with a number of TV and movie parts – such as his impressive performance as white supremacist gang leader AJ Weston in cult motorcycle series Sons of Anarchy, and starring role in comedy horror He Never Died. “I like the horror genre for acting,” he says. “Just because it’s so insane and you can just be a complete maniac. Like, ‘For the next twelve hours I’m gonna be a guy who scoops eyeballs out of people’s heads!’ Which I did over the summer.”

He has hosted various radio shows – from the now defunct Harmony in My Head on Indie 103.1 to his current Fanatic show on KCRW – contributed to regular columns for magazines like Vanity Fair, LA Weekly and the Huffington Post, written numerous books and published them on his own imprint 2.13.61, and toured the world with his dynamic spoken-word shows. And he shows no signs of slowing down.

Your drive and work ethic is unparalleled. I think it was your manager that said you just can’t stay still. Yes, that’s a woman called Heidi who works at my office. She’s an extraordinary woman and she said at one point, ‘You’re running away, you’re touring so much, you’re avoiding yourself! You just got a new house, try sitting and living in it.’ So I got off the road for about a year. The house was nice, I live in it alone and it looks like a stupid man cave with a stereo. It’s a safe environment and I don’t like that. My books are there, my records are there, I can get work done, but I prefer working on a notepad on an economy seat at the back of an airplane, which I was doing two days ago coming back from Antarctica. I’d rather be out in the world. I’ve got ten days before the tour starts and I will have to go out every night and instead of listening to my stereo I will listen to my little iPod in Starbucks for two hours and write in my notebook just so I can have movement. I figured this out: I’m addicted to movement, to getting out.

What is it about stillness that’s so hard to deal with? It’s like getting high on ether, which I’ve never done, but apparently if you get one inhalation too much it kills you. The house is like a comfy coffin and I’m afraid if I sit on this couch too long I won’t be able to get up. I’d much rather be out in the cold with a gig, with an itinerary. Like, ‘Okay you got an hour and forty-five minutes before the show starts, this is your ‘me time’ so enjoy it, figure that out, compartmentalise away from the show for a minute, listen to this album, enjoy it, and then get it together and get out there and hit it, because this is the best show you’re ever going to do until the next one.’ I’d rather be under that kind of scrutiny and compression. I feel like a calf being trotted to the slaughter when I’m not being challenged. I’m an angry person, I’m mad, and not at you or anybody – well there are a few people I’m mad at. I just kind of work and do everything out of fury.

Work is a coping mechanism? Yeah. I medicate with work. I constantly drink coffee and music kind of takes you out of yourself, you know? Let’s just put on this record and not want to break something. The idea of going on vacation – I just don’t understand that. Like, go sit on a beach? Am I that dead?

So when you’ve come back from war zones or developing countries and you’ve seen heavy shit – soldiers who’ve lost limbs and spoken to children who’ve been abducted – how do you process this and stop it from haunting you? By going out again. It’s the stillness that makes you go nuts. Living and travelling at a high rate and at some kind of velocity, where you’re seeing big stuff, stuff that kind of hits you like a gut punch, it’s kind of hard to come down from that.

I don’t know if you’ve ever met kind of older rock photographers? They’re all kind of nutty. Jim Marshall, the famous rock photographer, was a good buddy of mine. He did every famous Hendrix shot. You’ve seen more of his photos than you might understand. He was a lunatic because he’s still trying to come down from taking photos of Malcolm X, Miles Davis, Martin Luther King, Ornette Coleman and Jim Morrison. He walked around with all of that. I think when you live loudly or when you see a lot of stuff it’s very hard to just walk around with it. I have a hard time with it sometimes. I live alone and being alone is a very good coping mechanism.

What’s left to do? I gotta get to the North Pole. Just been to the South Pole. Definitely more countries in Africa I need to get to. A lot more travelling. At this point, at fifty-five years of age, I want to listen to a lot more music and I want to see a lot more parts of the world. Those are the two biggest things on the list.

When you’ve seen the effect of globalisation firsthand, through all your travelling, and you’ve seen the results of conflict, how does it make you feel about your own country? We’re Darth Vader. We’re the Death Star. We will kill you all. We are worse than ISIS and Al Qaeda. Corporations kill more than any terrorists do and we’re the biggest gang on the block and eventually we’ll toxify the whole planet and everything will die.

I meet wonderful people in this country all the time but I don’t know about what ‘WE’ do in our country’s name. It’s horrific. There’s been a concerted effort to dumb down Americans decade after decade after decade. Why? Because it fills prisons – which is a multi-billion dollar enterprise – and it fills battlefields, and it empties schools. And when people like you and I say, ‘Let’s empty the prisons and battlefields and fill the schools,’ they say, ‘You’re a socialist-communist!’ And I say, ‘Spell or define either.’ That’s the problem with America. They’ve been told they’re great, and they’re not. They’ve been told they’re exceptional and you can’t be exceptional when you do all this stuff. You’re just a person who didn’t get enough Sly & the Family Stone albums. You’re just a person who didn’t get enough Mark Twain.

You might like

Capturing what life is really like at Mexico’s border with the USA

Border Documents — Across four years, Arturo Soto photographed life in Juárez, the city of his father’s youth, to create a portrait of urban and societal change, memory, and fluid national identity.

Written by: Miss Rosen

In search of resistance and rebellion in São Tomé & Príncipe’s street theatre culture

Tragédia — A new photobook by Nicola Lo Calzo explores the historical legacy found within the archipelago’s traditional performance art, which is rooted in centuries of colonial oppression and the resilience of people fighting against it.

Written by: Miss Rosen

As Kneecap and Bob Vylan face outcry, who really deserves to see justice?

Street Justice — Standing in for regular newsletter columnist Emma Garland, Huck’s Hard Feelings host Rob Kazandjian reflects on splatters of strange catharsis in sport and culture, while urging that the bigger picture remains at the forefront of people’s minds.

Written by: Robert Kazandjian

Alex Kazemi’s Y2K period novel reminds us that the manosphere is nothing new

New Millennium Boyz — Replete with MTV and endless band t-shirt references, the book follows three teenage boys living in 1999 USA as they descend into a pit of darkness. We spoke to its author about masculinity, the accelerated aging of teenagers, and the rebirth of subcultures in the algorithm age.

Written by: Isaac Muk

Inside New York’s underground ’60s & ’70s cruising scene

Cruising in the Shadows — For gay men in the pre-Liberation era, The Ramble in Central Park was a secretive hotspot to find love and connection. Arthur Tress was there to capture the glances, gestures and pleasures.

Written by: Miss Rosen

Inside the weird world of audio porn

Porn without pictures — Storyline-driven and ethical, imageless erotica exploded during the pandemic. Jess Thomson speaks to the creators behind the microphones.

Written by: Jess Thomson