The awkwardness of becoming a teen, laid bare

- Text by Betsy Schneider

- Photography by Betsy Schneider

When I was in art school, I worked as a live-in nanny for four kids. I loved them all intensely, throwing myself into their lives, and eventually decided to combine that with the other passion in my life: photography.

I had known them for probably six or seven years when I began to see the youngest two children – identical twins – as my main subject matter.

As they grew, they became androgynous athletic girls. People thought they were boys and they kind of flowed into that phase of pre-adolescence.

Lydia

Allen

I became interested in this idea of transition – how we change throughout childhood – but especially what it means to have expectations change around you. When your body changes, how people treat you changes – as does the way we see and project ourselves.

That interest probably stems from my father (a psychologist and an amateur photographer) who was fascinated in both personal stories and in marking, acknowledging and basically making a big deal out of transitions.

When I turned 10, he told me that the next time I would add another digit to my age would be in 90 years when I turned 100. I was so freaking sad that whole day.

Calvin

Adele

Years later, after having kids of my own and photographing them obsessively, I started to realise that I was afraid of my kids growing up. Up until that point, I had felt so confident about parenting… but quickly became terrified of my oldest child Madeline becoming a teenager.

That doubt felt profound a year or two later, as she turned 11, when I fell in love with a woman and decided to leave my husband. Any chance of her having a somewhat normal transition into adolescence was kind of fucked up.

I watched her and my partner’s son, Sebastien (who was just a few months younger), go through this dual transition of their families changing while being in sixth grade – which, as a kid, had been the absolute hardest year of all for me.

Madeline

William

I suddenly realised that I had made my fear manifest, so I did what any self-respecting artist would do: figure out how to make art out of it.

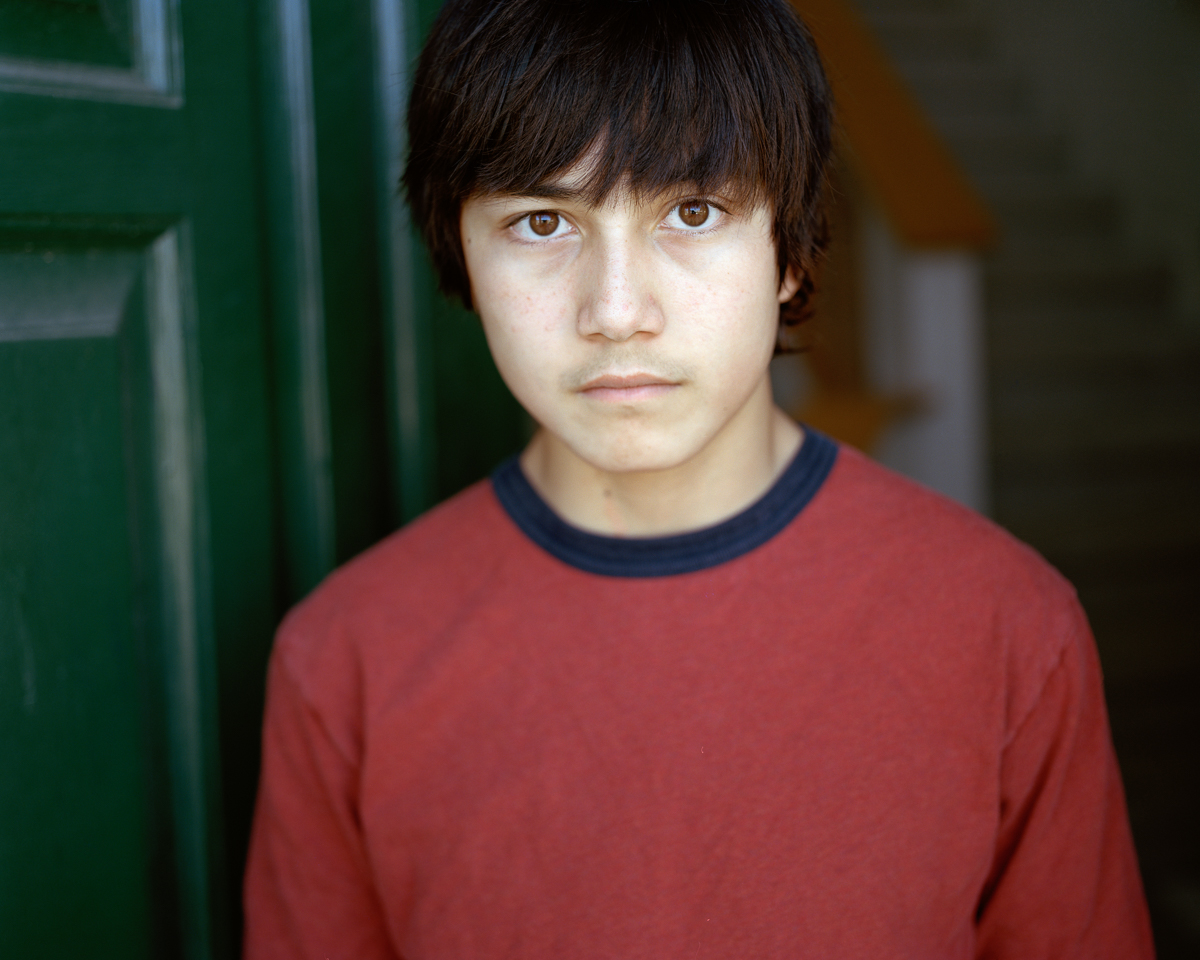

I decided to create still portraits and video of 250 13-year-olds, motivated by the intensity, complexity and beauty of that point in life.

Part of the inspiration was the idea that our 13-year-old selves stay with us for our whole lives. I remember quite profoundly what it felt like to be that age. That uncomfortable, scrawny, boyish girl with scraped knees who didn’t feel like she fit in is still inside me.

Okay, so now I’m a 51-year-old, scrawny woman who doesn’t feel like she fits in – but I guess I’ve buried it a bit and can deal with it better than I could back then.

Dayna

Jack

I originally took to photography when, in middle school, I got chosen to be a yearbook photographer. I think the teacher thought, ‘Betsy’s new and kind of uncomfortable, I’ll pick her.’

My father and my mother’s father were both avid photographers, so they helped me build a darkroom in the closet off our bathroom.

But in high school, I got pulled into being a runner. I became a jock and, for some reason, believed that one couldn’t be an artist and an athlete, so I stopped doing photography.

I always thought that I’d get back to it. It just took a lot longer than I thought: it wasn’t until the end of college that I realised not only could I do it, but I that it was what I had to do.

So when I say I finally figured out how to make art out of my life, I’m being a bit flippant – trust me, it was heart-wrenching.

But as I began to think a lot about the idea of being 13, I had also been getting in touch with people I knew from that age – the way middle-aged people do when they reconnect with old friends over Facebook.

Sienna

Owen

We started trading stories, many more painful than what I was consciously aware of. That, mixed with what I was watching my daughter go through, made me think, ‘This is what I need to photograph.’

In 2011, I got a Guggenheim Fellowship to do the project – the same year that Madeleine and Sebastien turned 13 – and it all started to come together simultaneously. Because of those old high-school friends, I had a head start in finding kids to photograph. Their friends, classmates and teammates – as well schools and after-school clubs – formed the project’s base.

I would make five exposures with each person and, since it was a view camera, they never knew exactly when I was taking the picture – so I could wait a bit until they were more relaxed.

I have what I’ve always called a Bill Clinton-esque need to be liked, so I would bend over backwards to try to gain their trust. I can also be a bit clumsy, which can mean I’m still very much a kid in some ways, and for the most part I think they appreciated my vulnerability.

Ausette

Ricardo

I often told them that I wasn’t trying to prove anything with either the images or the videos – and that I didn’t have an agenda… or, if I did, it was to prove that 13-year-olds were interesting. (I made sure they knew it wasn’t their responsibility to do that, but mine.)

Generally speaking, I found the boys to be the most interesting, engaging and vulnerable – not across the board; there were dull, closed-off boys as well as many compelling girls. They were subconsciously aware in a way I hadn’t expected.

I also found that this generation is easier to photograph than, say, my generation. These kids were comfortable in front of a camera; much more image-aware – which can be a bad thing too, because they have this idea of how they want to be seen. It was almost impossible to get some of them not to have a fake smile.

Still, I tried to let them lead somewhat so they felt part of the decisions. Often I think it made the picture better than it would have been had I maintained total control.

For instance, there was a boy who wanted to be photographed in a skateboard store with bad lighting while posing in what I felt was a cliché way.

Halle

Joss

I took it to humour him and then made some other pictures outside the store but, surprisingly, that picture ended up being one of my favourites of the whole project.

One girl talked about her fantasy of being an old woman who ran though shopping malls naked to embarrass her grandchildren. One boy told me he thought I was stealing the identities of 250 13-year-olds. (I think he might have meant stealing the souls, which sounds even more insidious).

Then there were the kids who opened up themselves for the brief time we were together yet, when I ran into them later, would not acknowledge me.

Maybe they genuinely did forget me – ultimately it was I think more profound for me than it was for them – but it was as if there had been a pact that what happened at the shoot stayed at the shoot.

Olivia

Jackson

Early on, I was struck by how my college students (at Arizona State University) responded so intensely to the pictures and the videos. They seemed to feel a real deep empathy. I think the experience of being 13 was so much closer for them than I’d imagined.

As I write this, the bulk of kids who participated in the project are about to graduate. I’m really excited to hear their responses to seeing their early adolescent selves – though there is some anxiety too.

My daughter doesn’t like the picture of herself – she thinks she looks too harsh and, well, she does – but that one doesn’t bother me. There are others where I do feel that tension of the trust that someone puts in you when they pose for a picture.

I try to think about it in a couple of ways. One is whether it’s good art or not. Before everything else, the question is whether the picture works. And then there is the ethical dilemma of what the picture is saying.

I have been able to get these kids to open up to me and I do feel a responsibility. I don’t want ridicule to be any part of this conversation.

But I also think that if the kids are awkward or have bad skin, it’s more about the age or something that I feel resonates.

That’s often hard for people to get about art photography: it’s not about glamour (although of course that can be a tool); instead I would say it’s about ideas, meaning and connection.

Trevor

Evangeline

I’m sure that several kids will see the book and feel embarrassed, but I also think back to those college students and how they usually recognise themselves in the pictures with a great deal of compassion. They think, ‘Wow, that was a really uncomfortable time… Glad I’m not there any more.’

To make a good picture, you have to care about your subjects – and you are always quite literally turning your subjects into an object.

It’s my picture, my interpretation and my perspective. I just hope that I afford depth and meaning. But to quote, weirdly, Courtney Love: “It takes a certain kind of person to want to impose your view of the world on others.”

Along the way, I’ve learned a few this from this project. I learned a lesson I keep learning and forgetting: that everything takes longer than you think it will.

Alex

I’ve learned a bit about photographing people I don’t know and about where my talent lies. I thought I wanted to make super systematic pictures – but I am just not that person.

I’m impulsive and intuitive and inconsistent. That’s who I am and what I have to offer. And that those traits can be useful.

I’ve also learned to be happy with that and just go with it. Maybe I kind of exorcised some doubts from when I was 13. Maybe not. We’ll see.

To Be Thirteen will be published by Radius Books and the Phoenix Art Museum in September. An accompanying exhibition will launch at the Phoenix Art Museum in May 2018.

Find out more about photographer Betsy Schneider.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.

You might like

As Kneecap and Bob Vylan face outcry, who really deserves to see justice?

Street Justice — Standing in for regular newsletter columnist Emma Garland, Huck’s Hard Feelings host Rob Kazandjian reflects on splatters of strange catharsis in sport and culture, while urging that the bigger picture remains at the forefront of people’s minds.

Written by: Robert Kazandjian

Alex Kazemi’s Y2K period novel reminds us that the manosphere is nothing new

New Millennium Boyz — Replete with MTV and endless band t-shirt references, the book follows three teenage boys living in 1999 USA as they descend into a pit of darkness. We spoke to its author about masculinity, the accelerated aging of teenagers, and the rebirth of subcultures in the algorithm age.

Written by: Isaac Muk

In photos: The people of Glastonbury’s queer heart The NYC Downlow

Elation and family — Once a year, a meatpacking warehouse nightclub springs up in Glastonbury’s South East corner and becomes a site of pilgrimage for the festival’s LGBTQ+ scene. We met the people who make The NYC Downlow so special.

Written by: Isaac Muk

Inside the weird world of audio porn

Porn without pictures — Storyline-driven and ethical, imageless erotica exploded during the pandemic. Jess Thomson speaks to the creators behind the microphones.

Written by: Jess Thomson

Coming of age in New York’s ’70s punk heyday

I Feel Famous — Through photographs, club flyers and handwritten diary entries, Angela Jaeger’s new monograph revisits the birth of the city’s underground scene, while capturing its DIY, anti-establishment spirit.

Written by: Miss Rosen

We are all Mia Khalifa

How humour, therapy and community help Huck's latest cover star control her narrative.

Written by: Alya Mooro