The Travel Diary: Confronting the shocking violence of Honduras

- Text by Sean Hawkey

- Photography by Sean Hawkey

I was born in Honduras, Tegucigalpa in the aftermath of Hurricane Mitch in 1999. A year later, my family moved to Brighton in the UK, where I have since spent most of my life.

From a young age, I’d heard a lot about the problems in Central America – especially in Honduras, which is often called the “most violent country in the world.” Growing up, I couldn’t understand what was driving people to behave this way or where this violence was coming from.

This year, after turning 18, I returned to Honduras for two weeks to find out more about my country of birth. Even though my Spanish is a bit broken and I wear very British clothes, it was only my shock that made me feel out of place. My reactions were very British, but the Hondurans took almost no notice of the extreme violence that was on display. They’ve been exposed to it all their lives – it’s everywhere.

The body of mormon missionary, Jonothan Ordonez, 27, lay covered with a blanket on a road close to the City’s University UNAH after his murder, 12th August 2017.

Ricky Alexander Zelaya Camacho was arrested by the Anti-Extortion Police in Tegucigalpa and presented to the press. The notorious 18th Street Gang is known to be responsible for rape, extortion, murder, torture and drug-related offences. 10th August 2017.

The first crime scene I saw was a 6-month-old baby girl, who had been crushed between rocks near a river. I also spent some time outside the forensics morgue, where the family of a 16-year-old girl was told she had been raped and killed by a gang. Although seeing their bodies was disturbing, it was the mourning families hit me a lot harder. It made me realise that I fear loss more than I fear death.

Most news stories have a lifespan. Honduras has been a violent country for a very long time, and when there is no major change, news networks don’t want to know. The people at the forefront of trying to create change are students, who are being blocked from education by the government because of a biased teaching system. With a new government, a new generation of students can be taught to help create change within the country.

For me, taking photos is a way of providing insight into a hidden world – of giving a voice to those who cannot speak, and report on the unreported. Honduras is a broken country. It needs radical change. If this next election [happening on November 26] doesn’t go well and another government who does next to nothing to try and fix these problems gets into power, a lot more innocent people will die.

The family of a 15-year-old girl have just learned that she had been raped, tortured and killed. Her body was found tied up in the woods, it is thought she was killed by a gang. 3rd August 2017.

RIot Police await orders to move forward into the UNAH University and begin firing tear gas cannisters into the crowds of protesting students. 10th August 2017.

A 16-year-old girl, arrested for extortion, is presented to the press by the police in Tegucigalpa. Teenagers in Honduras are often used to carry out extortion for gangs, their family’s lives are threatened if they do not cooperate. If they are caught, like this girl, they will go to prison for taking part in the crime. 9th August 2017.

A worker at the Forensics Morgue in Tegucigalpa picks up a decapitated head from the back of a pickup truck. 7th August 2017.

Students at the UNAH university protest frequently, taking over the main road in front of the university. 10th August 2017.

A forensics team working to document the death of taxi driver José Manuel Moradel, 45, murder in the street. 45 bullet shells were found at the scene. 8th August 2017.

The coffin of a baby is removed from the forensic morgue in Tegucigalpa. 11th August 2017.

The two sons of a murdered taxi driver weep in the street at the sight of their father’s motionless body. 8th August 2017.

Text has been edited for length and clarity.

See more of Sean Hawkey’s work on his official website.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.

Latest on Huck

Baghdad’s first skatepark set to open next week

Make Life Skate Life — Opening to the public on February 1, it will be located at the Ministry of Youth and Sports in the city centre and free-of-charge to use.

Written by: Isaac Muk

Nydia Blas explores Black power and pride via family portraits

Love, You Came from Greatness — For her first major monograph, the photographer and educator returned to her hometown of Ithaca, New York, to create a layered, intergenerational portrait of its African American families and community.

Written by: Miss Rosen

Meet the muxes of Juchitán, Mexico’s Indigenous third gender

Zapotec folk — Having existed since the pre-colonial era in southeast Oaxaca state, a global rise in LGBTQ+ hate is seeing an age-old culture face increasing scrutiny. Now, the community is organising in response, and looking for a space to call their own.

Written by: Peter Yeung

Russian hacktivists are using CCTV networks to protest Putin

Putin’s Jail — In Kurt Caviezel’s project using publicly accessible surveillance networks from around the world, he spotlights messages of resistance spread among the cameras of its biggest country.

Written by: Laura Witucka

Inside the world’s only inhabited art gallery

The MAAM Metropoliz — Since gaining official acceptance, a former salami factory turned art squat has become a fully-fledged museum. Its existence has provided secure housing to a community who would have struggled to find it otherwise.

Written by: Gaia Neiman

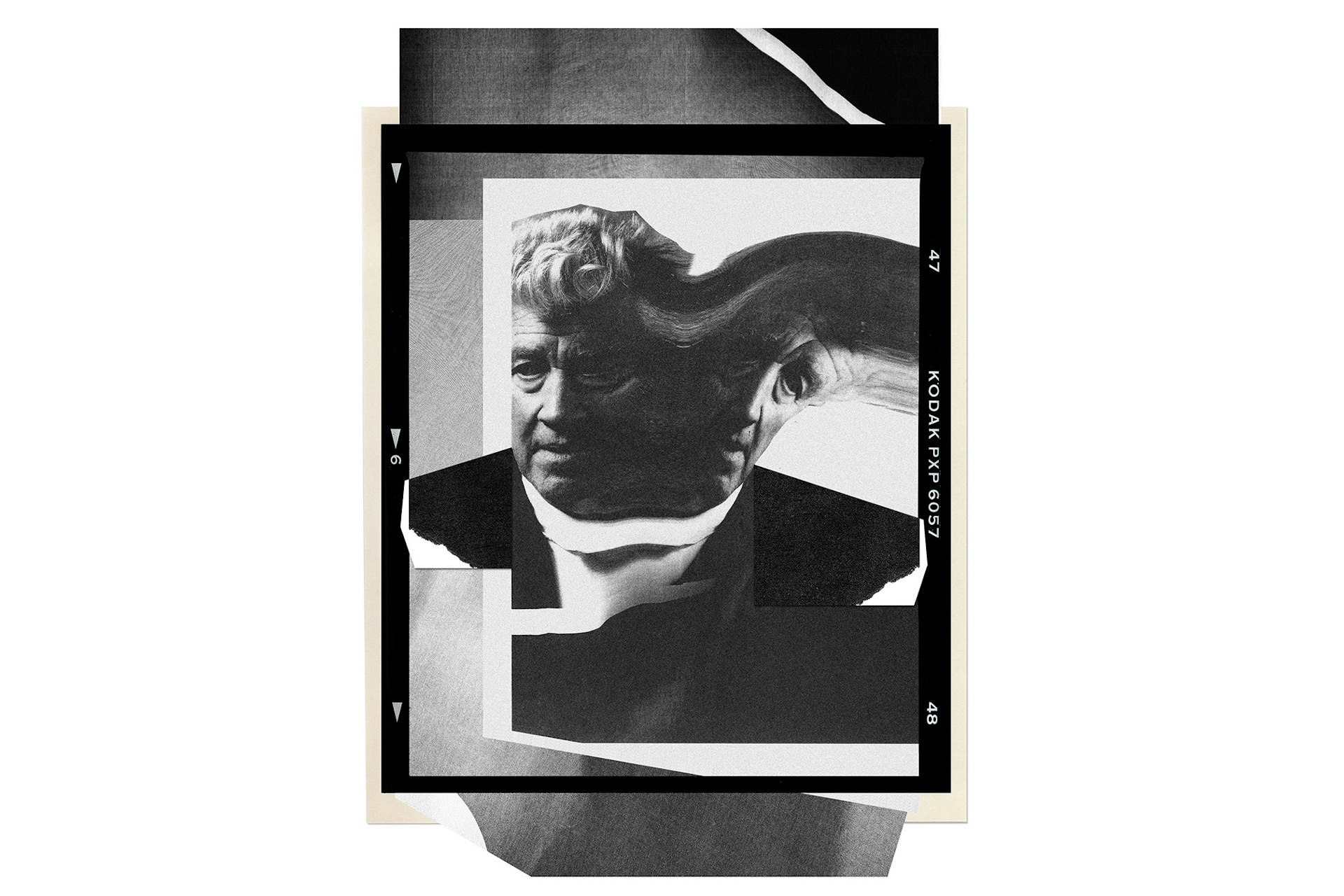

Ideas were everything to David Lynch

Dreamweaver — On Thursday, January 16, one of the world’s greatest filmmakers passed away at the age of 78. To commemorate his legacy, we are publishing a feature exploring his singular creative vision and collaborative style online for the first time.

Written by: Daniel Dylan Wray