We must abolish the police to create a more equal society

- Text by Koshka Duff and Connor Woodman

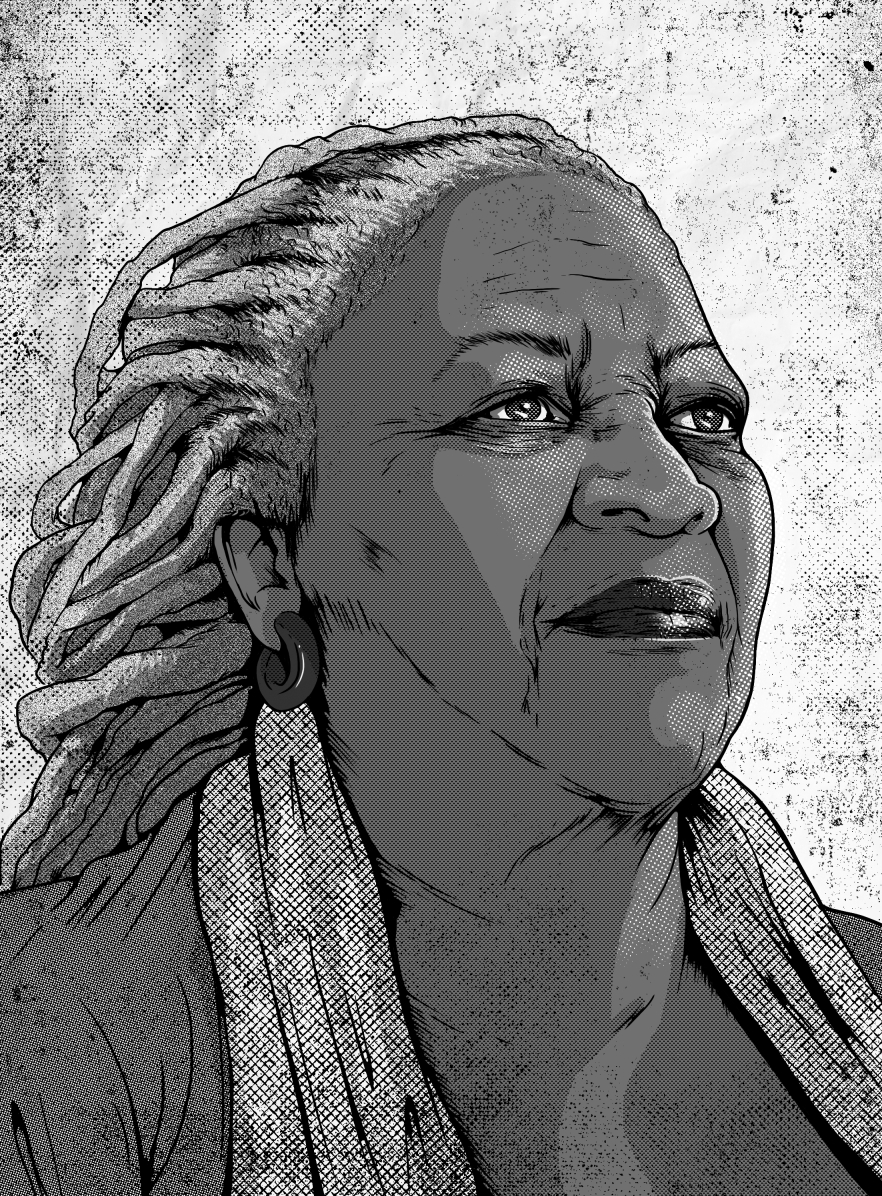

- Illustrations by Cat Sims

In June earlier this year, Lisa Bender, the Minneapolis City Council President, made a statement to hundreds of protesters. “Our efforts at incremental reform have failed,” she said, “Period.” In the wake of the killing of George Floyd, which sparked global demonstrations for Black Lives Matter, Bender’s pledge to dismantle the Minneapolis Police was a moment of hope for activists around the world.

Although Bender’s pledge is still no closer to becoming policy, the idea of abolishing the police – which may once have seemed preposterous – is gaining mainstream currency. It seems that many share the suspicion that there is something rotten about the police, not just as individuals, but as an institution. And not just as one isolated institution, but as the tip of a much larger iceberg of coercive institutions, all of which work to criminalise, subdue, and punish.

Policing, in this broader sense, includes the whole criminal punishment system of courts, prisons, juvenile detention facilities, and electronic tagging. It includes the mechanisms of border enforcement such as detention centres, walls and barbed wire fences, and chartered deportation flights.

It creeps into the most intimate aspects of life in the form of mass and targeted surveillance, and it spreads beyond state boundaries in the form of colonial and neo-colonial ‘counter-insurgency’ operations, the ‘pacification’ of unruly populations, and the ‘extraordinary rendition’ of terror suspects.

While the forms of policing are various, they all make the same claim: we are here to keep the peace; you need us to keep you safe. Meanwhile, they enact some of the most elaborate and systematic, if not sadistic, forms of violence that humans have ever devised.

Notoriously, moreover, they enact this violence most regularly and most vigorously against those at the sharp end of the unjust hierarchies – of race, class, gender, sexuality, and disability – that stratify our society.

If you are Black in Britain, you are at least nine times more likely to be stopped and searched than a white person is. During the three months of lockdown, around one in three young Black men in London were stopped and searched by the Metropolitan Police. People of colour make up 12 per cent of the UK’s general population, but 27 per cent of its prison population – rising to over 50 per cent for children’s prisons.

The number of BAME people who suffer death at the hands of British police is so concerning that even the UN has sounded the alarm. Look at a court case in the UK, and you will, in all likelihood, find an array of plummy judges and lawyers accosting a working-class defendant, often one who has been disciplined, let down, and traumatised by every major institution throughout their life, from school, to the family, to social workers, and the ‘care’ system.

These are not accidental disparities that could be corrected through improved guidelines or cultural sensitivity training. They are products of police and prisons’ very purpose in society, the very reason they were developed. Since their invention in the early 1800s, the police have been used for racial and class control: as slave patrols in the US South, as strike-breakers in industrial England, as colonial enforcers in Ireland, Kenya and elsewhere.

Every emancipatory movement – be it anti-racist, anti-capitalist, environmentalist, or LGBTQ+ – tends sooner or later to come up against the police. The ongoing revelations that police officers infiltrated nearly every significant social movement and progressive organisation in recent British history, spying on the most intimate aspects of their targets’ lives, attest to this.

However benevolent a face it may present, the essence of policing in practice has always been the threat and use of violence to enforce the prevailing social order – to protect the ‘haves’ and their accumulated wealth and power from the ‘have-nots’ who might contest it.

It is unsurprising, then, that policing has always been met with resistance. The anti-police protests that have radiated outwards from Minneapolis following the murder of Floyd are just the most recent manifestations of a longstanding and justified antipathy towards policing’s oppressive power that is widespread among those sections of society that actually experience it.

But while they did not come out of nowhere, these uprisings have achieved something remarkable and new. As Black Lives Matter co-founder Patrisse Cullors put it: “This is the first time we are seeing… a conversation about defunding, and some people having a conversation about abolishing the police and prison state. This must be what it felt like when people were talking about abolishing slavery.”

Just as slavery was once perceived as necessary and natural, the idea of a society without police and prisons is, for many, unthinkable. There is a deeply ingrained sense that these institutions are necessary, however distasteful they may be.

The question is, necessary for what? Clearly, the police are necessary to our current form of society. A world where the poor burn in a tower block as the rich sweep trillions into off-shore havens is a world that needs police and prisons to uphold these rank inequalities.

An abolitionist perspective is not one that imagines, naively, that the police could be abolished in isolation while everything else carries on as normal. Abolitionism is a perspective that challenges us to ask: what about society would have to change in order that such immense levels of normalised violence would no longer be required to maintain it?

But still we face the question: what would you replace them with? To this we respond, firstly, that the core function of the police – to subdue, warehouse and brutalise the poor, the downwardly racialised, the non-conforming, to maintain our profoundly unequal and crisis-ridden social order and repress any challenges to it – is not one we think worth replacing, in any form.

Nonetheless, there are some genuinely valuable social roles currently placed on the shoulders of the police that could be performed much better by alternative, more caring institutions.

The police are often the first port of call when people are suffering from acute mental health crises, for example. Yet, quite evidently, an institution characterised by cuffs and restraint, violence and submission – the infliction of further trauma – is not best placed to intervene positively in these situations. Certainly, policing does nothing to prevent such scenarios from arising again.

Similarly, intimate partner violence and sexual assault are products of deeply-embedded patriarchal norms, reinforced by an economic order in which leaving a violent partner or standing up to a harassing boss can leave you destitute. Rather than assisting women in this position, the criminal punishment system is often arrayed against them. Four in five women in prison have suffered domestic violence and or sexual abuse outside of it.

A system that strip-searches tens of thousands of people every year, incarcerates and abuses migrant women in detention camps, and reflects a notorious macho culture, simply intensifies the patriarchal power relations at the root of the problem.

Abolitionists seek not just to eradicate the police and prison estate. We seek to transform the conditions that generate the serious and pervasive forms of social harm that police claim to deal with but in reality tend to exacerbate and feed.

This is a huge task, of course, but the first step is to move beyond the simplistic logic of crime and punishment. Homelessness, knife and gun violence – most if not all of the real social problems that police are currently tasked with responding to – can be better addressed by means other than ramming them under the carpet with the force of a police baton.

Pre-order your copy of Abolishing the Police (An Illustrated Introduction), from Dog Section Press, by donating to the book’s crowdfunder.

Follow Dog Section Press on Twitter.

Follow Cat Sims on Instagram and Twitter.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.

You might like

Jeremy Corbyn confirms new party with Zarah Sultana: “Change is coming”

A real alternative? — Sultana revealed that she was quitting the Labour Party yesterday evening, saying that she was going to co-lead a new party with the former Labour leader.

Written by: Isaac Muk

There have never been only two sexes — intersex people exist

Hemaphrodite Logic — Juliana Gleeson’s new book explores the intersex movement from 1990-2025. In this exclusive extract, the author outlines intersex liberation as an “unlikely offspring” of feminist and gay/lesbian struggles.

Written by: Juliana Gleeson

Misan Harriman: “The humanity I bear witness to is extraordinary”

Shoot the People — Following the premiere of a new film exploring the photographer’s work and driving forces, we caught up with him to chat about his rapid rise, shooting protests and the need for powerful documentarians in times of struggle.

Written by: Isaac Muk

Transphobia is the main reason why people ‘detransition’, according to new survey

Transphobia’s toll — The largest ever survey of its kind found that just 9% of respondents had "gone back to living as their sex assigned at birth at least for a little while at some point in their lives”, with the biggest reason being discrimination, harassment and being shunned by friends and families.

Written by: Ella Glossop

Campaigners hack UK bus ads on Father’s Day to demand Alaa Abd El-Fattah’s release

A father behind bars — Placing posters at bus stops around London, Leeds and Manchester, they called for greater action from foreign secretary David Lammy to reunite the British-Egyptian activist with his son and family.

Written by: Isaac Muk

Jack Johnson

Letting It All Out — Jack Johnson’s latest record, Sleep Through The Static, is more powerful and thought provoking than his entire back catalogue put together. At its core, two themes stand out: war and the environment. HUCK pays a visit to Jack’s solar-powered Casa Verde, in Los Angeles, to speak about his new album, climate change, politics, family and the beauty of doing things your own way.

Written by: Tim Donnelly